The Egyptian civilization began 5,000 years ago and lasted for 3,000 years.

Even though it was an exceptionally stable and relatively unchanging civilization, it is nearly impossible—unless one is a specialist—to give an overview of such a long span of history.

In this section, we will focus only on topics related to the mystery of the pyramids and mathematics.

Dynastic Periods of Ancient Egyptian Civilization

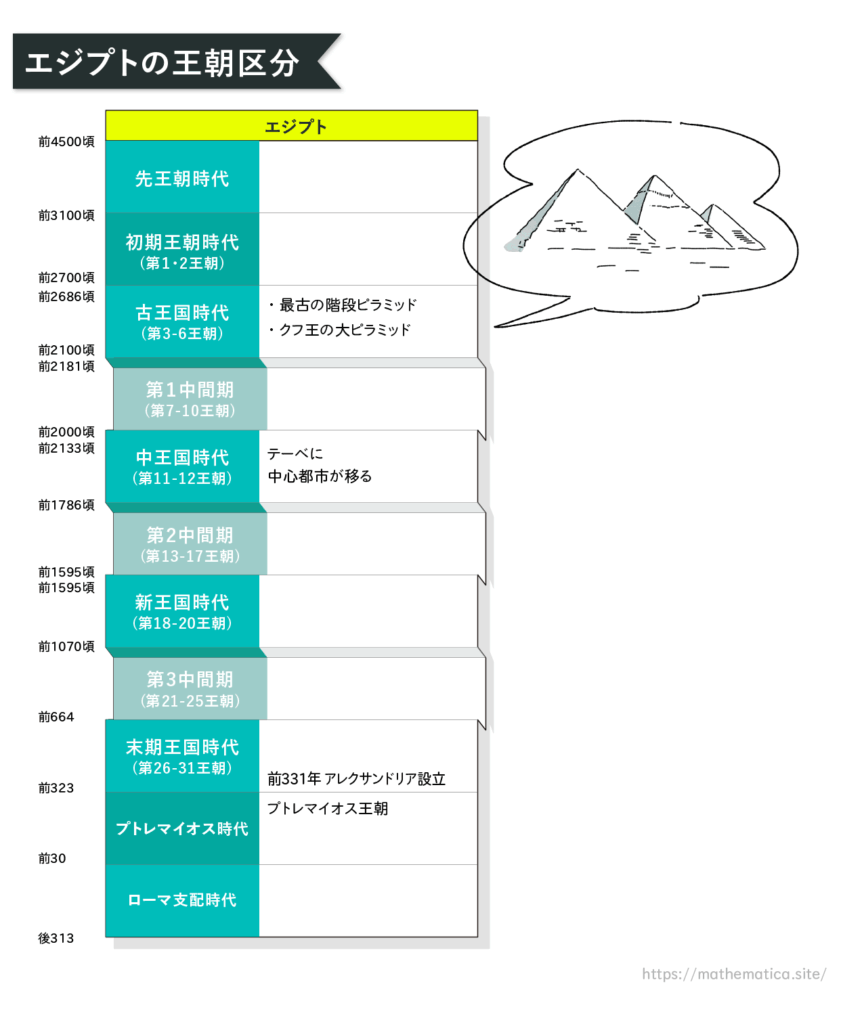

At the end of section “2-1. The Nile and Egyptian Civilization,” we briefly outlined the historical periods of Egypt. Here, let us take a closer look.

While the details may vary slightly depending on the researcher, we will use the following simplified classification.

This dynastic table is based on the History of Egypt, written in Greek by the Egyptian priest Manetho in the early 3rd century BCE and presented to Ptolemy II, who ruled Egypt at the time. During this period, Egypt was under the control of a Greek dynasty, and the pharaohs were of Greek origin.

Although the original manuscript of History of Egypt has not survived, excerpts were quoted in several later works, allowing scholars to reconstruct its contents. These records have also been compared with inscriptions on temple corridors and historical documents preserved in temples throughout Egypt. Over time, historians have adjusted and refined the chronology accordingly.

The names of pharaohs are listed for each dynasty, and while some rulers are said to have reigned for several centuries or are of questionable historical existence, it is remarkable how such a long record has been preserved over a span of 3,000 years.

The Great Pyramid, which is the central topic of this series, was constructed during the Old Kingdom, a period often referred to as the “Pyramid Age.” In this section, we will briefly touch upon the Old Kingdom, with further details to be explored in Chapter 5.

Early Dynastic Period: Historical Traditions from a Time with Few Written Records

Egyptian civilization begins with the Early Dynastic Period, when Egypt was first unified as a single state. Before this unification, as discussed in 2-1. The Nile and Egyptian Civilization, the Nile Valley had been divided into many nomes (provinces), each led by a religious leader. The head of each nome was elevated to the status of a divine figure and held absolute authority. As the nomes grew larger, conflicts among them also began to emerge. However, unlike other regions in the ancient Near East, these nomes did not develop into city-states with defensive walls and autonomous government. Instead, the nomes were gradually integrated into larger national entities.

Although there were likely battles before unification, the process of integration does not appear to have involved domination or subjugation, as was often the case in later periods. Instead, integration seems to have occurred without discrimination. This is also evident in the myths mentioned earlier: conflicts between tribes were seen as conflicts between their guardian deities, and the victorious gods did not enslave the defeated ones but rather merged with them or were regarded as the same deity. Since the Egyptian people were agriculturalists, they all worshipped the sun, which led to the sun having many names.

By around 3300 BCE, there were two unified kingdoms in Egypt: Lower Egypt in the fertile Nile Delta, and Upper Egypt, extending upstream to the area near the First Cataract. Eventually, a dynasty emerged that united these two kingdoms. This became the First Dynasty, and the First and Second Dynasties are collectively referred to as the Early Dynastic Period. This era served as a transition between the prehistoric period and the Old Kingdom, gradually establishing the foundations of a centralized state.

Lower Egypt, with its rich delta, was a prosperous land. In general Near Eastern history, poor nations often invaded wealthier ones. Likewise, in Egyptian history, it appears that Upper Egypt—poorer and more inland—often conquered Lower Egypt. Interestingly, in modern history, it was usually the more developed Western powers that colonized less developed Asian nations, but in ancient history, the reverse pattern often occurred.

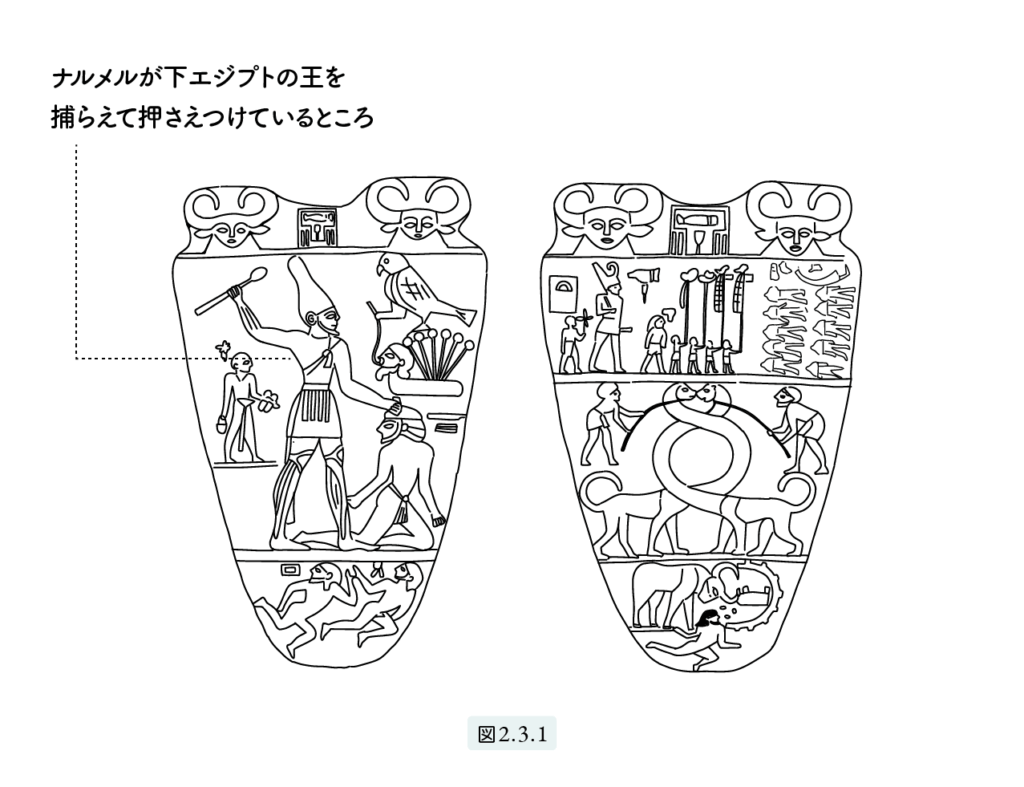

The Narmer Palette

The Early Dynastic Period was still an age of oral traditions, with few written records. Around 3100 BCE, a king from Upper Egypt unified Upper and Lower Egypt, becoming the first ruler of the First Dynasty. One of the most famous artifacts from this period is the Narmer Palette, shown in Figure 2.3.1. Based on this palette, many scholars believe that Narmer was the first king of unified Egypt.

As those who have seen Egyptian statues or wall paintings may know, Egyptian makeup is especially distinctive around the eyes—bold eyeliner and shadow are prominent features. A cosmetic palette was a stone slab used for grinding minerals such as malachite into powder to make eye makeup, and these palettes were often decorated with elaborate carvings.

On the Narmer Palette, King Narmer is depicted capturing and subduing the king of Lower Egypt, already shown with divine authority and majesty. It also shows the chiefs of the nomes following behind, holding staffs topped with totems. Based on their attire, these figures are believed to be Libyans.

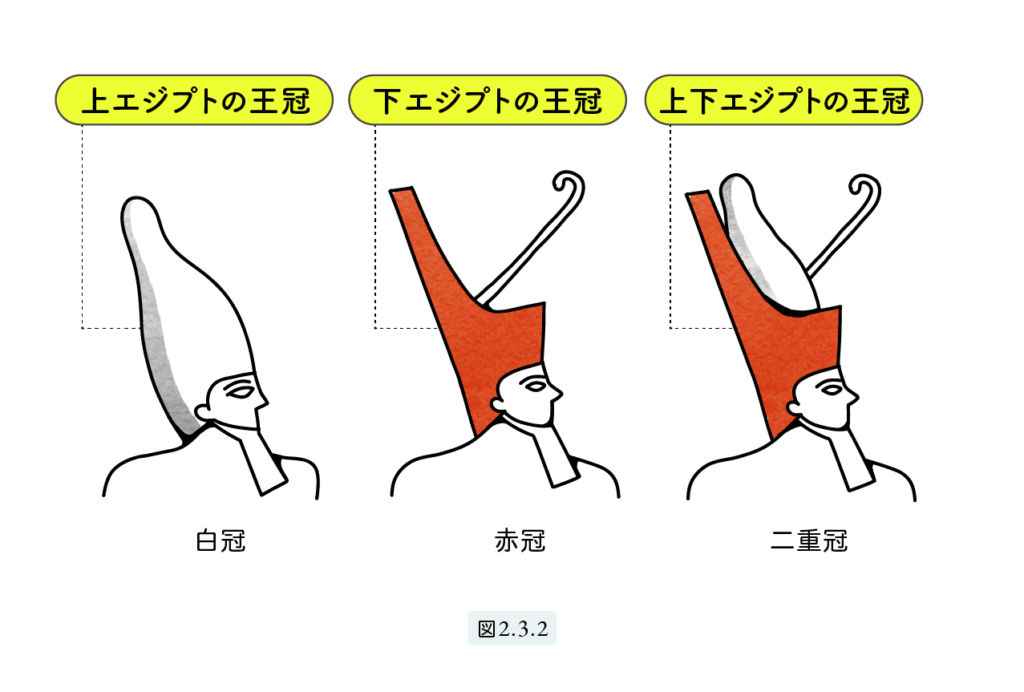

White Crown, Red Crown, and Double Crown

Although Upper Egypt conquered Lower Egypt, Egypt did not become the sole domain of Upper Egypt. Throughout the history of Egyptian civilization, the Pharaoh was always regarded as the ruler of the unified lands of Upper and Lower Egypt. As a symbol of this unity, the Pharaoh wore the Double Crown, which combined the White Crown of Upper Egypt (symbolized by the falcon totem) and the Red Crown of Lower Egypt (symbolized by the cobra totem). See Figure 2.3.2.

The Pharaoh as a Deified Figure

Over time, Egypt became ethnically homogeneous. Even migrants, after a hundred years, would assimilate into society. As a result, the vast majority of the population shared a similar status as farmers. Among agrarian communities, cooperation was often more productive than domination. As tribes and nomoi (districts) grew, those with larger populations and greater labor forces naturally gained more power. Warfare was primarily a means to increase labor power (i.e., population), and for a Pharaoh to lead effectively, charisma and the ability to attract people were essential. In other words, Pharaohs did not rule the people by force—they were revered by the people as divine beings.

The Old Kingdom: The Youth of Egyptian Civilization and the Invention of Writing

The Old Kingdom: The Youth of Egyptian Civilization and the Invention of Writing

The Old Kingdom marks the youth of Egyptian civilization—a vibrant and dynamic period filled with innovation. Among its many achievements, the invention of writing was particularly significant. It is also believed that mathematics emerged during this time. As mentioned earlier, this is the era in which the iconic Great Pyramid was constructed, which is why the period is often called the “Pyramid Age.”

By the 3rd Dynasty, Egypt’s economy had developed further, and the nation grew increasingly wealthy. Initially, the Pharaoh was merely associated with the falcon god, but by this time, he came to be equated with the sun god himself. The 4th Dynasty saw the peak of pyramid construction, with King Khufu’s Great Pyramid being the most colossal. It is composed of approximately 2.3 million stone blocks, each weighing about 2.5 tons on average, amounting to a total of 6 million tons of stone. Napoleon once remarked that such an amount of stone could build a wall around all of France.

Undertaking such a grand project required massive resources, including manpower, food, tools, and a powerful bureaucratic system capable of calculating and managing costs. The precise alignment, surveying, and engineering of a perfect square pyramid also suggest that mathematics and related scientific knowledge made tremendous advances during this era. In addition to pyramids, the artistry and uniqueness of the Old Kingdom can also be seen in the sculptures, bas-reliefs, and paintings found in temples and mortuary complexes, as well as in furniture and decorative crafts.

In the 5th Dynasty, pyramids continued to be built, though they were much smaller in scale than those of the previous dynasty. However, this does not necessarily mean that royal authority weakened or that architectural skills declined. It is possible that interest shifted from pyramid construction to temple architecture, or that there was a change in religious beliefs among the people.

By the 6th Dynasty, the bureaucracy became bloated and increasingly complex. The number of officials grew, priesthoods gained more power, and the central government could no longer sustain itself. Although pyramids were still built, the quality of stonework clearly declined, and many pyramids collapsed into rubble over time.

Egyptian civilization spanned a vast period of time. Even a single dynasty could last more than a century. The Old Kingdom alone endured for 500 years. Yet no prosperity lasts forever. Long famines could trigger economic decline. Since Pharaohs were not merely representatives of gods but regarded as gods themselves, natural disasters called their divinity into question. In ancient times, when a divine king was believed to have lost the ability to maintain cosmic order, he could even be killed by his own people. By the end of the Old Kingdom, pyramid construction diminished in scale and eventually ceased. Power increasingly fell into the hands of viziers, the authority of the central government weakened, and the country entered the First Intermediate Period.

Egyptian history alternates between periods of centralization and decentralization—known as Kingdoms and Intermediate Periods, respectively. Kingdoms are times of prosperity, while Intermediate Periods are marked by stagnation. Interestingly, these phases often correspond closely with developments in Mesopotamian civilization. One explanation for this is global climatic shifts. The water level of the Nile was significantly higher during the Old Kingdom than during the First Intermediate Period. This suggests that the climate was wetter and more favorable for agriculture during the Old Kingdom, whereas the Intermediate Period was marked by arid conditions and frequent famines.

The same trend is observed in the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. In times of regional disaster, waves of refugees were created, who then attacked prosperous towns. These waves gradually spread over wide areas across many years, prompting large-scale migrations of peoples. Such population movements were common in Mesopotamia as well.

The First Intermediate Period: The Rise of Local Nobles (Nomarchs)

With the beginning of the First Intermediate Period, nomadic tribes began to invade repeatedly from the desert, and the Delta region was temporarily occupied by Asian migrants. However, the main cause of turmoil during the First Intermediate Period was internal conflict, not invasions by foreign powers. At this time, external forces such as Mesopotamia or the eastern Mediterranean states were not yet strong enough to pose an organized threat to Egypt.

As the First Intermediate Period progressed, the various privileges of the central pharaoh began to shift into the hands of local nobles (nomarchs). Eventually, these nomarchs began to proclaim themselves as kings. The 7th to 10th Dynasties are considered part of the First Intermediate Period. According to Manetho, during the 7th Dynasty, 70 kings ruled over the course of just 70 days. Over time, the 11th Dynasty, which originated in Thebes—a small village during the Old Kingdom—gradually expanded its power. The fourth pharaoh of this dynasty eventually succeeded in reunifying Egypt.

About Dynasty Classifications:

Dynastic tables vary slightly depending on the researcher. For example, some classify the 11th Dynasty as spanning both the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, considering the unification achieved by the fifth pharaoh of the 11th Dynasty as the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. In this article, however, we simply categorize the 11th Dynasty under the Middle Kingdom. Especially during intermediate periods, it is common for multiple dynasties to coexist, making clear distinctions difficult to establish.

The Middle Kingdom: A Golden Age of Literature and Mathematics

The fourth pharaoh of the 11th Dynasty is regarded as the founder of the Middle Kingdom. In Egyptian history, it was customary for Upper Egypt in the south to conquer Lower Egypt in the north, and this time was no exception. The town of Thebes in Lower Egypt developed into the royal capital. On a hill overlooking Thebes from the west bank of the Nile, grand mortuary temples adorned with colonnades and massive stone structures were built, symbolizing the revival of the ancient Egyptian concept that “the king is a god.”

By the Early Dynastic Period, the Egyptians had already begun keeping records using written characters. These were the sacred hieroglyphs—highly artistic, but too cumbersome for daily use. During the Middle Kingdom, a new script called “hieratic” was developed, more practical for everyday administration and record-keeping.

The Middle Kingdom represents the midpoint of Egyptian civilization and marks a period of maturity. Centralization of power progressed, and a well-structured bureaucratic system emerged. It was the scribes, as civil servants, who managed Egyptian society. This era was also a golden age of literature, during which many of Egypt’s literary masterpieces were written. In the schools for scribes, both literature and mathematics were taught. As is often said, “mathematics is a language.” In Mesopotamia, mathematical texts appeared only after the invention of writing and the spread of epic poetry and storytelling. Likewise, the original texts of the “Rhind Papyrus” and the “Moscow Papyrus,” both key sources of ancient Egyptian mathematics, are thought to have been written during this time—further suggesting a close link between language and mathematics.

Documents such as letters and accounting records show that agricultural yields were high and wealth reached even the lower classes. Life and culture during this period were highly developed and prosperous. Some of the excavated materials from ancient archives include what appear to be “maps” and “travel guides,” suggesting that many Egyptians traveled abroad. Egypt was no longer a closed society; diplomacy and trade flourished, and the process of internationalization had begun.

Egypt was not the only civilization flourishing at this time. Across Mesopotamia, Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and the eastern Mediterranean, numerous city-states and kingdoms arose, and conflicts became increasingly common. Until this point, Egypt had been spared foreign invasions thanks to its favorable geography. However, the ancient Near East was undergoing dramatic change. Groups known as Indo-Europeans began to infiltrate from the north, triggering large-scale migrations within the region. Egypt could no longer remain unaffected.

In Mesopotamia, many kingdoms rose and fell, and a remarkable number of city-states existed. Still, none had yet grown powerful enough to break through the closed nature of Egyptian civilization. Egypt continued to cling to its time-honored traditions and unique cultural identity.

Second Intermediate Period: Foreign Rule and the Transformation of Egypt

As the Middle Kingdom gradually declined, domestic unrest grew, and local nobles began to assert power. From early in the Middle Kingdom, people of Asian origin—referred to as the Amorites—had slowly begun to enter Egypt. Initially, they peacefully integrated into Egyptian society, but by the time of the Second Intermediate Period, they came to dominate the eastern part of the Delta region.

During this time, a large-scale upheaval affected the entire Western Asian region, triggering further waves of migration. Egypt could no longer remain isolated within its closed world. In hieroglyphic documents, these intruders were referred to as the Hyksos, meaning “foreign rulers” or “shepherd kings.” The Hyksos were largely composed of Amorite peoples of Asian origin, but some members of the Indo-European peoples—ancestors of the later Greeks—also appear to have been among them. This is inferred from Indo-European elements in royal names and pottery designs. It is believed that the Hyksos were a multi-ethnic, mixed group. The Second Intermediate Period marks the first time Egypt fell under foreign rule, lasting for about 200 years.

From the Hyksos, the Egyptians learned about horses and chariots, as well as methods of warfare. Until then, Egypt had been protected by its geography and had little experience with large-scale wars against foreign powers. It was a bureaucratic state governed by capable civil servants, with no territorial ambitions and no standing army. Accustomed to peace, Egypt had grown complacent. Meanwhile, the rest of the ancient Near East had turned into a battlefield where great powers vied for dominance. Egypt, caught in this turmoil, saw waves of migrants—Hyksos—invade the Delta and endured the humiliation of foreign rule for generations.

Having lived in peace, Egypt’s military power was fragile. The Hyksos introduced advanced weaponry and military techniques—horses, chariots, and composite bows—and, most importantly, the brutal reality of “true warfare.” However, aside from military advancements, the Hyksos contributed little else. Their kings, recognizing the superiority of Egyptian civilization, sought to assimilate. They adopted the title of Pharaoh and continued the tradition of royal dynasties.

Hyksos rule forced Egypt to drastically shift its direction. With strong ties to Western Asia, the Hyksos pulled Egypt out of its insular existence along the Nile and onto the broader stage of the ancient Near East. From this point onward, Egypt would act not as an isolated kingdom, but as a key player within the greater Oriental world.

Conclusion

The “Ancient Egyptian Mathematics” covered in this series was developed during the Old Kingdom and transcribed during the Second Intermediate Period. The Great Pyramids were also constructed during the Old Kingdom. Therefore, in the context of this series, our exploration of Egyptian history will conclude here.

Of course, Egypt’s history does not end at this point. In the New Kingdom, Egypt begins a resurgence. Once again, local nobles from Thebes unify the entire country and establish a new dynasty. The pharaohs cross national borders and launch military campaigns into Asia, transforming Egypt into a “world empire.”

However, from this point on, Egypt’s history can no longer be viewed in isolation. It must be understood within the complex web of international relations involving the Mediterranean coast, Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and Mesopotamia.