The Social Role of Mathematics and Its Development:How Civilization and Mathematics Evolve Together

To unravel the mystery of the pyramids, one must understand the history of Egypt.

Did the ancient Egyptians possess a civilization advanced enough to grasp concepts like pi or the golden ratio?

Or was Egyptian mathematics—as previously believed—fundamental and primitive, making any connection to pi merely coincidental?

The purpose of this series is not simply to solve the puzzle of the pyramids.

It also aims to explore why mathematics emerged, how it came into being, and to show that mathematics has never existed in isolation.

Rather, it has evolved hand in hand with society, advancing alongside the development of civilization.

For this reason, understanding Egyptian history is essential.

It may also provide key insights into the pyramid mystery itself, offering a new perspective on how mathematics and society are deeply intertwined.

The Origins and Evolution of Civilization:A Historical Journey Through Human Evolution and Cultural Development

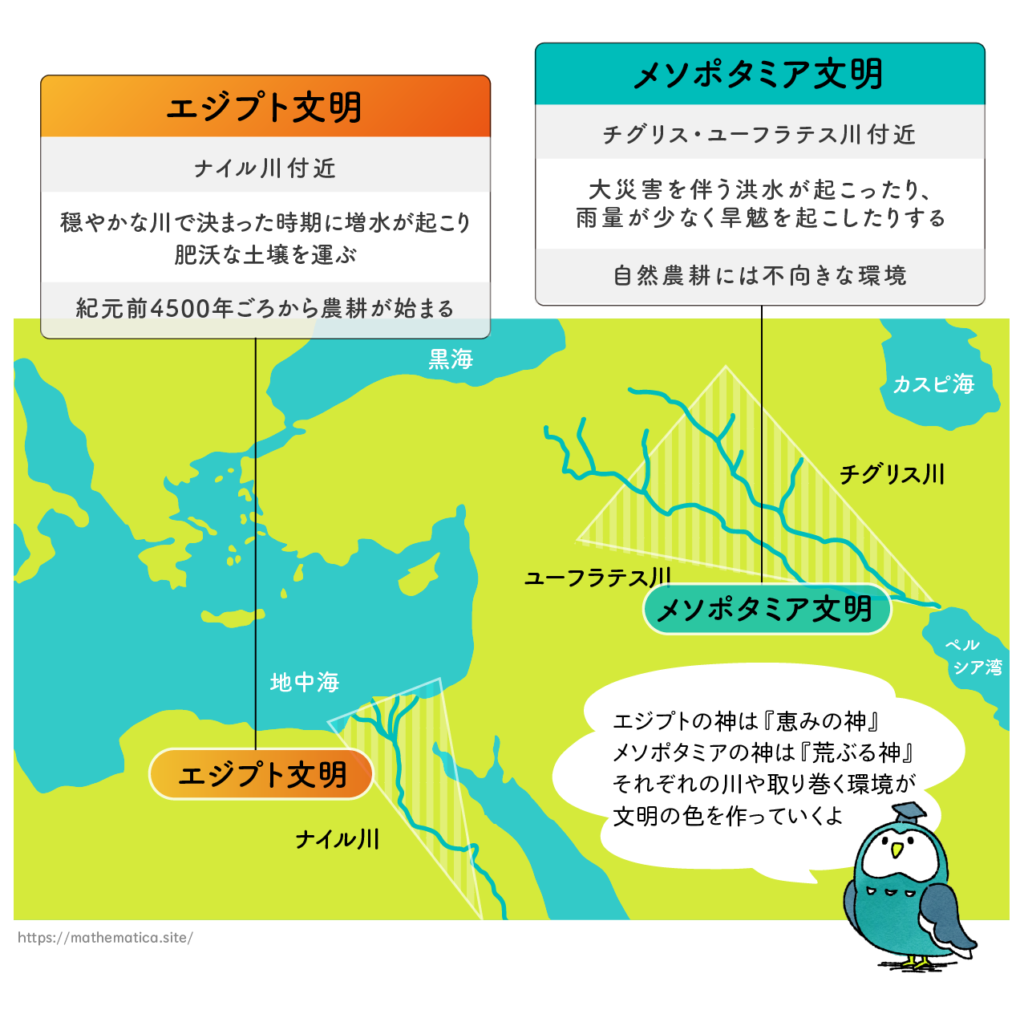

Egyptian civilization is thought to have emerged slightly later than Mesopotamian civilization, beginning to take shape around 5,000 years ago.

Both civilizations developed along the banks of great rivers. However, the nature of these rivers was quite different in Egypt and Mesopotamia, and this contrast profoundly influenced the development of each culture.

In particular, these differences are reflected in their respective cosmological views, especially in the field of astronomy.

As each civilization progressed, the unique characteristics of their environments became increasingly apparent.

Before we delve deeper into those differences, let us first explore how civilization itself began.

The Beginnings of Human Culture:Evolution and Environmental Shifts 10,000 Years Ago

It was only about 10,000 years ago—an instant in the long arc of human evolution—that humans began to develop primitive forms of culture.

The last Ice Age came to an end, and for a time the Earth experienced a warm and humid climate. Even the African continent was once covered in rich forests. Evidence of this can be seen in rock paintings and engravings found in what is now desert in the African savannah, depicting large mammals such as elephants, rhinoceroses, and giraffes.

Around 7000 BCE, a global aridification period began. Forests receded, and grasslands gradually transformed into steppes.

As parts of Africa—particularly regions that would become the Sahara Desert—grew uninhabitable, people began migrating in search of water, eventually settling along the Nile River.

For a long time, Egypt’s Neolithic period remained a historical blank spot. However, recent archaeological discoveries have begun to shed light on the gradual transition from a lifestyle based on hunting and gathering to one centered on agriculture and animal husbandry.

Migration and the Rise of Agricultural Culture:Settlers from Asia Around 4500 BCE

Around 4500 BCE, groups of migrants from Asia began joining the indigenous peoples of the Nile Valley.

They likely traveled either along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean or crossed the Red Sea by boat, eventually making their way to the Nile. It was during this period that agricultural culture began to emerge in Egypt.

Did agriculture originate in one specific location and then spread outward?

Current theories suggest that agriculture developed independently in several regions of Asia around the same time, though the question remains open to debate.

Interestingly, domesticated goats and sheep, as well as wheat varieties unearthed in Egyptian archaeological sites, appear to have originated in Western Asia.

The Rise and Pause of Civilization:Why Did Rapid Advancement Lead to Stagnation?The advancement of mathematics, science, and technology—or civilization as a whole—has never followed a smooth, linear path.

At times, rapid progress seems to occur all at once, only to be followed by long periods of stagnation.

Why does this happen?

Such sudden developments are often described as “revolutions.” For instance, the emergence of agricultural culture is known as the Agricultural Revolution.

This pattern of sudden growth followed by prolonged stagnation may be explained, in part, by the fact that inventions and discoveries are extremely rare, while the transmission of knowledge and technology tends to spread widely across regions and generations.

Egyptian mathematics, in particular, appears to have undergone a significant early development.

However, rather than evolving further or disappearing, it was preserved and passed down in essentially the same form for centuries.

Influence from Mesopotamia: The Transmission of Sumerian and Mesopotamian Civilization to Egypt

Around the same time in Mesopotamia, the Sumerians began settling near the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, laying the foundations for Mesopotamian civilization. It is believed that the same Sumerians—or their ancestors—may have also reached Egypt by way of the Red Sea. This theory is supported by striking similarities in cultural artifacts, such as Mesopotamia’s distinctive cylinder seals, artistic crafts, and architectural styles using sun-dried bricks.

However, even if there was an influence from Asia, it was likely limited to the very early stages of Egypt’s civilization. Afterward, Egypt, protected by its geographically isolated landscape, developed a unique and self-contained culture. This civilization maintained its distinct style with remarkable tenacity and rarely sought change.

Expansion of Communities and the Formation of Tribes: Irrigation, Agriculture, and the Drive Toward Greater Efficiency and Cohesion

In the era of hunting and gathering, early humans—like other animals—formed small, mobile groups centered around mothers. Because the number of game animals was limited, these groups had to remain far apart from one another. Over time, people began to make their living along the Nile River through fishing and grain cultivation. This shift led to a more settled lifestyle, and the groups gradually grew larger. Still, society remained matrilineal, centered around kinship ties. These kin-based groups are called clans.

Eventually, they learned that by constructing canals and practicing irrigation, they could grow grain more efficiently. Irrigation projects and farming tasks became more effective when undertaken by larger groups. Several related clans would unite to form a tribe, and tribes would form alliances to create even larger communities. These communities occupied areas known as nomes. A nome was a regional social unit, similar to a modern-day prefecture or province.

Each clan worshiped a divine animal that symbolized their ancestral lineage—this guardian spirit was called a totem. A nome, being a coalition of clans, also had its own totem, which was typically the totem of the most powerful clan within the region.

The Emergence of Kingship: The Pharaoh and the Rulers of Egypt

Around this time, it seems that there were people in ancient Egypt whose clothing and appearance differed from the native Egyptians. One such group is believed to have been Libyans who arrived along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. From the upper reaches of the Nile, Nubians are thought to have come, bringing with them elements of Black African culture.

Agriculture in Egypt began around 4500 BCE. As the climate grew increasingly arid and the population expanded, primitive farming methods could no longer sustain society. Irrigation channels had to be built to divert water from the Nile, and trenches for irrigation needed to be constructed as well. Disputes over water rights likely arose between neighboring clans, sometimes escalating into conflict. In both irrigation projects and warfare, larger groups held the advantage, and as these groups grew, they required leaders to unify and direct them.

Related clans began to band together, forming alliances that eventually developed into territorial units known as nomes. Within these nomes, systems of kingship began to emerge. Thus was born the Egyptian king—the Pharaoh.

The Nile and the Tigris-Euphrates: Predictable Floods vs. Turbulent Floods

Egyptian Civilization and the Nile vs. Mesopotamian Civilization and the Tigris-Euphrates: A Tale of Two Rivers

Egyptian civilization flourished along the Nile River, while Mesopotamian civilization developed around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. The key differences between these two great civilizations can largely be attributed to the contrasting natures of their rivers.

The Nile is a remarkably gentle and reliable river. Like clockwork, it floods at the same time every year, bringing fertile soil from the upper regions, then gradually recedes in a predictable pattern. Though it is called a flood, the rise in water level is moderate, and people had time to move to higher ground before it occurred.

In contrast, the Tigris and Euphrates are wild and unruly rivers, frequently causing catastrophic floods. The memory of these floods is preserved in the legend of Noah’s Ark. The reason lies in the rivers’ sources: the Nile originates in the tropical rainforest, where rainfall is abundant, consistent, and predictable. The Tigris and Euphrates originate in the mountainous regions of Turkey, where rainfall and snowmelt can vary dramatically from year to year. Some years brought droughts; others, devastating floods.

Pharaohs in Egypt constantly observed the heavens to predict when the Nile would flood. Devices called Nilometers were installed to measure the river’s depth. Before the inundation, they would dredge canals, repair embankments, and move tools and supplies to higher ground. As the waters rose, canal gates were opened to distribute the water to farmland. The rich silt brought by the floods would settle, making the soil so fertile that simply sowing seeds would guarantee an abundant harvest.

When the water level dropped, the excess water was drained back into the Nile, preventing salt buildup in the soil. This was a major difference from Mesopotamia, where irrigation water was left to evaporate, leading to increasing salinity and drastic declines in crop yields. The Mesopotamian rivers didn’t provide enough water to flush the salt back into the rivers.

In short, the Egyptian gods were seen as benevolent and generous, while the gods of Mesopotamia were regarded as fierce and capricious.

In Mesopotamia, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers were unpredictable, often flooding without warning. These floods left behind significant damage and demanded harsh labor for recovery. Unlike the more uniformly fertile lands along the Nile, Mesopotamian terrain varied greatly—fertile and barren land, low-lying flood-prone areas and safe highlands—which frequently led to disputes over water and territory. Competition for better land sparked constant conflicts. Villages were fortified, and each walled city developed its own political and economic systems, evolving into independent city-states. In Mesopotamia, numerous city-states existed simultaneously, and warfare was a constant feature of the region.

In contrast, ancient Egypt saw the development of religious cities with temples and royal palaces, but not fortified city-states.

These differences in the nature of the rivers brought about fundamental distinctions in worldview between the Egyptians and the Mesopotamians. Egyptians were drawn to permanence and universality. They believed that nature (or the gods) acted according to an unchanging, trustworthy order. As such, they showed little interest in irregular astronomical phenomena like solar and lunar eclipses or planetary motion. To them, humans were merely part of nature—not a superior or separate force. As evidenced by the totems, they believed their ancestors had taken the forms of animals such as dogs, ibises, or falcons. They revered animals like cattle, cats, and dogs; killing sacred creatures like the ibis could be punishable by death.

Egyptian kings gradually became deified. They were believed to control and harness nature (gods) by predicting the annual Nile floods and managing post-flood irrigation projects. Over time, the king became identified with the nomos totem, seen as a divine and inviolable figure.

Mesopotamian gods, on the other hand, were capricious—capable of bringing devastating floods or disasters at any moment. Humans, powerless before the forces of nature, lived in fear of these volatile gods. The king’s primary duty was to divine the gods’ intentions and appease them. Humans were created by the gods in their image to serve as laborers and providers of sustenance. Even the king was merely a servant of the gods—a priest who conveyed divine will to the people.

To interpret the gods’ will, divination flourished. The horoscope—astrological fortune-telling known today—originated in Mesopotamia. Unlike Egyptians, the Mesopotamians were fascinated by change and impermanence. They recorded solar and lunar eclipses and observed the distinct movements of planets such as Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Venus, and Mars, noting their differences from the fixed stars.

The Birth of Egyptian Civilization and the Role of the Nile River

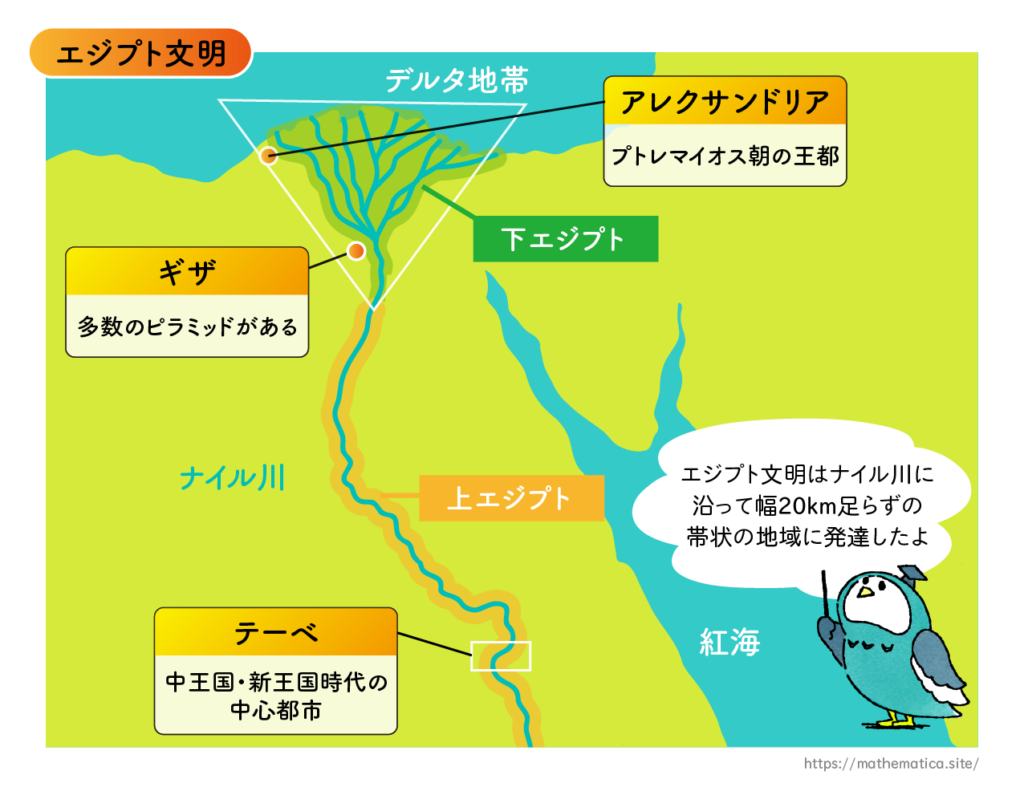

Let us take a moment to consider the geography of Egypt.

What most defines Egyptian civilization is the Nile River. Even today, 96% of Egypt is desert, and of the remaining 4%, only about 2.6% is arable land. Egyptian civilization developed along a narrow strip of land—less than 20 kilometers wide—that follows the Nile River. This fertile ribbon lies within the final 1,000 kilometers of the Nile’s vast 6,600-kilometer length.

In the context of the entire African continent, Egypt occupies only a small portion, yet it gave rise to one of the most remarkable civilizations in human history.

The lower reaches of the Nile form a low-lying triangular delta, known as the Nile Delta. At the base of this delta lies Giza, famed for its pyramids. The Nile River region is divided into Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt at Giza. On maps, north is typically shown at the top and south at the bottom, but in this context, “Upper” and “Lower” Egypt refer not to geographical orientation but to the flow of the river—whether it is upstream or downstream. Thus, the delta region is considered Lower Egypt, and the region to the south is Upper Egypt. Think of it as the opposite of typical map directions.

Along the Nile, there are points where the river narrows and the current becomes rapid—these are known as cataracts. The first and second cataracts mark such locations. In ancient times, the Egyptians considered “Egypt” to extend from the First Cataract in the south to the Nile Delta in the north. Between the First and Second Cataracts lies a region of undulating lowlands called Nubia. Further south beyond Nubia was the land of Kush, corresponding to present-day Ethiopia.

The Mother Nile and Egyptian Civilization: The Foundation of Civilization and Source of Life

The Nile River flows gently, and throughout the year, a steady wind blows from the Mediterranean in the north toward the upper reaches of the river. To travel upstream, one could simply set a sail on a papyrus reed boat and ride the north wind. For downstream travel, the current of the river would carry the boat. Although Egypt was a long, narrow, belt-like country, it was naturally unified by the great artery of the Nile. On both sides of the river stretched vast deserts that protected the land from foreign invasions. This geographical safety and seclusion gave rise to one of the longest-lasting and most stable civilizations in human history. The Egyptian people were truly a “people of the river,” living by the grace of their mother, the Nile.

When we think of ancient Egyptian civilization, we often imagine a land of deserts. But in truth, it was a riverine society—a civilization of the river. In the following discussion, we will refer to this unique world as the “Valley of the Nile”—not a valley surrounded by mountains, but one bordered by vast and desolate desert.

The Discovery of Mathematical Texts: The Rhind Papyrus and the Ahmes Papyrus

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Role of Scribes in Ancient Egyptian Civilization

Egyptian civilization lasted for an astonishing 3,000 years with very little change, maintaining a remarkably peaceful and stable society. (Of course, over such a long span, there were occasional changes and periods of unrest.) Several factors contributed to this stability: the deserts to the east and west provided natural protection, and the Nile River enabled easy travel throughout the land, minimizing regional differences. The people were generally mild-tempered, and the barter system, which required tolerance and cooperation, persisted for a long time.

However, the real key to this long-lasting stability is believed to be the competence of the high-ranking bureaucrats. Among these officials, the scribes were particularly powerful. Children of the nobility and priestly class began their education at the age of five in a scribe school called the “Per Ankh” (“House of Life”), where they studied writing and mathematics. There was a great deal to learn.

As the priests gradually gained more power, the royal authority tried to prevent power from becoming overly concentrated among them. To this end, the king issued documents encouraging children from a wide variety of professions and social classes to enroll in scribe schools. As a result, many children from diverse backgrounds were educated as scribes, helping to prevent the elite classes from monopolizing privilege.

Scribes were responsible for managing the economy, planning civil engineering works such as canals, and directing public projects. The foundation of these duties was record-keeping and mathematics. One of the most famous mathematical documents from ancient Egypt is the Rhind Papyrus, also known as the Ahmes Papyrus. It was discovered among the ruins of Thebes and later purchased by a British collector named Rhind, hence its name. The text was copied by a scribe named Ahmes around 1650 BCE, though it is believed to be based on an even older source dating back to around 1800 BCE.

In this way, ancient Egypt came to be one of the world’s first large, long-lasting, and centrally governed unified states. It was a powerful central state governed by a class of learned bureaucrats known as scribes. Wealth and power were heavily concentrated in the hands of the pharaoh, and nothing symbolizes this more than the construction of the pyramids.

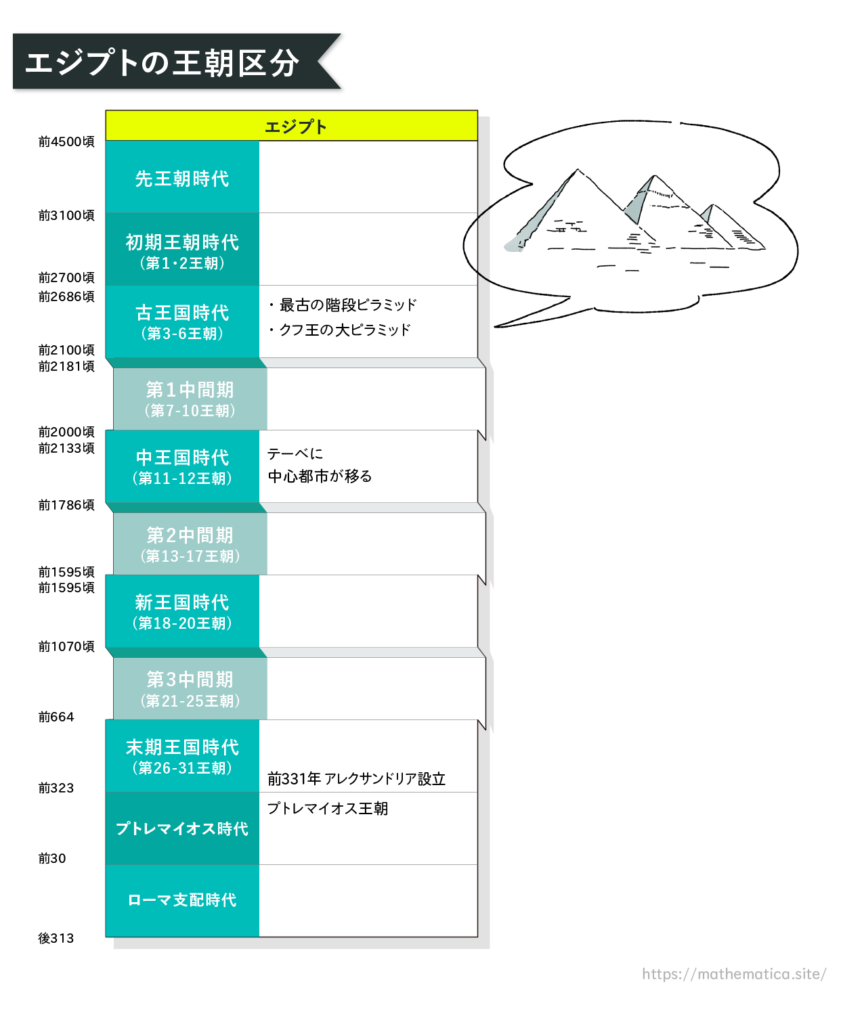

Chronological Periods and Overview of Egyptian Civilization

The Longevity and Decline of Egyptian Civilization

Egyptian civilization, for all its greatness, did not enjoy eternal prosperity. As the volume of the Nile’s waters decreased, agricultural productivity declined, and national strength weakened. In such times, the divine authority of the pharaoh began to erode.

The pyramids were originally built for the royal family alone, as monuments ensuring their eternal life in the heavens. Mummification was likewise reserved for royalty. However, over time, not only royalty but also nobles and priests began to seek eternal life, desiring large tombs and preservation as mummies. By the end of the Egyptian civilization, even wealthy commoners were commissioning their own mummies.

Therefore, by the time Herodotus visited Egypt, the people may have already begun to question the logic of building a massive pyramid for the sake of a single king.

While it is often said that Egyptian history is uniform and uneventful, the reality is that it spans over three thousand years. Summarizing it in full is no small task. In this series, we will highlight only the historical elements relevant to our theme.

Historians typically divide the history of ancient Egypt into the following periods:

In this context, the terms such as “Old Kingdom” refer to periods in which a unified dynasty ruled over all of Egypt, marking eras of political stability, economic prosperity, and centralized control. In contrast, the “First/Second/etc. Intermediate Period” designates times of fragmentation, when Egypt was divided among multiple dynasties or autonomous entities and was often plagued by internal conflict and turmoil.

Each historical period consists of multiple dynasties. The large square-based pyramids covered in this series were constructed during the Old Kingdom, specifically from the 3rd to the 6th Dynasties. The famous pyramids of Giza belong to the pharaohs of the 4th Dynasty.

The 1st and 2nd Dynasties of the Old Kingdom are commonly referred to as the Early Dynastic Period, while the era preceding the Old Kingdom is known as Prehistoric Egypt.

Conclusion

In this section, we traced the origins of Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, examining how they flourished and highlighting the geographical factors that shaped their development. By understanding the historical context and the daily lives of the people, we begin to see the broader picture of the knowledge and learning that were needed at the time.

In the next chapter, we will explore the worldview and cosmology of ancient peoples through the myths of ancient Egypt.