オシリス神話:ナイルの谷に集まる人々と守り神の部族

The Myth of Osiris: The People Gathering in the Nile Valley and Their Tribal Guardian Deities

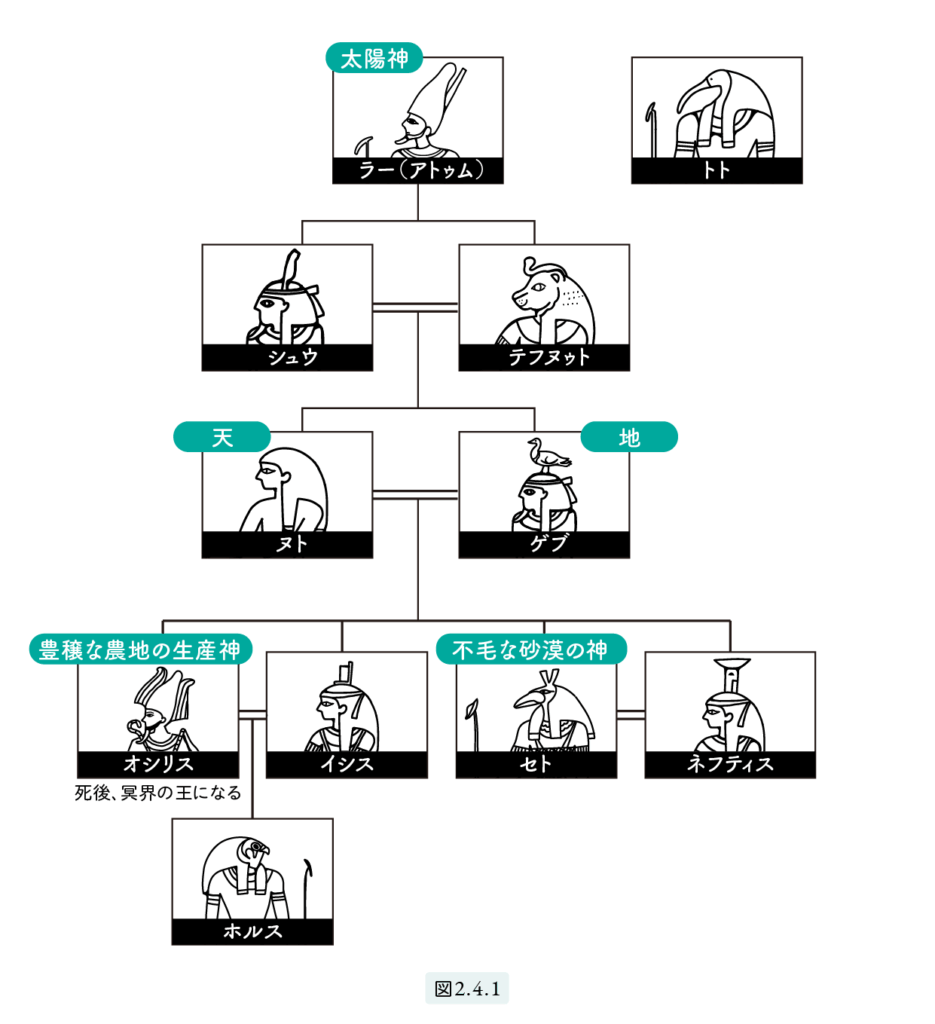

In this section, let us explore the myth of Osiris. To begin, let’s review the family relationships of Osiris. The central figures in this myth are Osiris, his wife Isis, their son Horus, and the antagonist Set. Nut, Geb, and Nephthys do not appear in this story. The sun god Ra and the wisdom god Thoth appear in supporting roles.

In the early stages of prehistory, many people from deep within Africa and from Asia gathered in the fertile Nile Valley in search of water. Each tribe had its own guardian deity. Among them, the tribe that worshipped the falcon as their guardian deity is believed by experts to have had strong military capabilities and likely originated as hunting tribes from the Libyan region. Among the falcon gods, the most powerful was the god Horus.

On the other hand, Osiris was a god of agriculture, believed to have come from Asia—possibly the region of Syria—and spread throughout the Nile Valley. Sun gods were also common deities among agricultural peoples. Among them, the sun god Ra is thought to have come via the Mediterranean from the Caucasus region. Isis was an ancient goddess from the Delta region of Lower Egypt, while Set is believed to have been a god of Upper Egypt, possibly originating from the Libyan region.

These gods (i.e., the tribes that worshipped them) did not engage in systematic conquest of others; rather, they lived peacefully as neighboring peoples. Over time, however, the tribes that worshipped Horus began to gain power. There were apparently many such Horus-worshipping tribes, and it is said that at least fifteen distinct forms of Horus can be identified.

The Beginning of the Osiris Myth, with Horus as Its Guardian Deity

As we saw in Section 2-2: Creation Myths of the Universe, the ancient Egyptians did not attempt to organize their myths into logically coherent narratives. However, the Osiris myth stands out as a well-structured and consistent story. This is largely because it was recorded in the work On Isis and Osiris, written by the Roman author Plutarch during the period when Egypt had become a province of the Roman Empire and the ancient Egyptian civilization was on the verge of disappearing.

The Osiris myth is a story centered on Horus, the falcon god, who was originally a guardian deity of a particular tribe, no different from other tribal gods. As the tribe grew stronger and began to dominate neighboring groups, its influence expanded. At the time, battles heavily depended on the decisiveness and bravery of leaders. The falcon, soaring high into the sky, seemed to merge with the heavens, appearing as a divine being of the sky. Victory in battle was directly associated with the falcon, which came to symbolize power and triumph. Eventually, the tribe’s leader was seen as an incarnation of the falcon endowed with divine power.

In the beginning, Horus did not belong to any creation myth. The creation myths were those of agrarian societies that worshipped deities representing the fertility of the land. In contrast, Horus emerged from a warrior tribe with a mythos rooted in conquest. However, as tribes merged and Horus gained widespread popularity, the priests at major religious centers began to fear that their own gods would be overshadowed by Horus. In response, they incorporated Horus into their own myths. At the same time, the tribe that worshipped Horus likely sought inclusion in the dominant religious narrative.

Thus, Horus became the son of Osiris and Isis, introducing human-like familial relationships into the pantheon of gods. In this way, the Osiris myth evolved—shifting from the story of a single tribe to a royal myth, undergoing significant transformation throughout history.

The Myth of Osiris

The Children of Nut and Geb

Let us now begin the myth of Osiris. Nut, the sky goddess, and Geb, the earth god, had four children: Osiris, Set, Isis, and Nephthys. Set was Osiris’s younger brother, while Isis and Nephthys were their sisters. Osiris married his sister Isis.

Osiris was the god of fertility and agriculture, associated with the rich and productive farmlands. In contrast, Set was the god of the barren desert.

The Conflict Between Osiris and Set

Osiris inherited the throne from Nut and became a wise king, worshipped by all the people on Earth. His younger brother Set, jealous of Osiris’s popularity and power, plotted to usurp the throne.

Osiris would regularly travel around the country with gods and musicians to perform rituals praying for the peace and prosperity of the land. During his absence, Isis, with the help of Osiris’s minister Thoth, would protect the kingdom. Set tried to seduce Isis during these times, but she rejected him completely.

One day, upon Osiris’s return from his ceremonial journey, Set invited him to a banquet. At the feast, Set jokingly suggested that Osiris try lying in a large, beautifully crafted wooden box (a coffin). The moment Osiris lay inside, Set slammed the lid shut, nailed it closed, and cast it into the Nile River.

Isis’s Resolve

Upon hearing the news, Isis, the wife of Osiris, cut off her hair, dressed in mourning clothes, and set off on a journey to recover her husband’s body. After enduring many hardships, she finally found the chest containing Osiris’s remains.

Fearing what would happen if Set discovered her, she secretly returned to her homeland in the Delta and hid near the marshes. Though Osiris was dead, she believed she might be able to bring him back to life with her magic.

Transforming herself into a kite (a type of bird of prey), Isis circled above Osiris’s body. Indeed, Isis was a great sorceress. Even though Osiris was dead, she miraculously conceived his child.

Set’s Transformation and Isis’s Imprisonment

Set also possessed divine powers. Sensing that something was amiss, he transformed himself into a jackal and searched the area around the marshes. By chance, he discovered the chest containing his brother’s body.

Fearing that Isis might use her magic to revive Osiris, Set tore the body into fourteen pieces and scattered them across Egypt. Once again, Isis set out on a journey to recover her husband’s remains.

Each time she found a part of the body, she performed funeral rites and built a shrine in that location. However, this was a deception meant to trick Set into believing the remains had been buried separately. In truth, she treated each piece with embalming rituals and secretly brought them back together.

When she returned to the marshes of the Delta, she was captured by Set and imprisoned. Fortunately, she was able to hide both the fact that she had recovered the remains of Osiris and that she was carrying his child, without Set realizing it.

The Resurrection of Osiris

With the help of Thoth, Isis escaped from prison. She gave birth to Horus safely.

Then, she reassembled Osiris’s hidden remains, anointed them with sacred oils, and performed the ritual of resurrection. Through her powerful magic, Osiris came back to life.

However, Osiris no longer belonged to the world of the living. Though he could have reclaimed the throne, he chose instead to become the king of the underworld, the realm of the dead. He entrusted the earthly throne to Horus, the son born after his death.

The Sun Spell and the Resurrection of Horus

One day, Isis left her child Horus alone in the marsh while she went out.

A magical barrier had been cast over the marsh to prevent anyone from entering.

However, Set transformed himself into a venomous snake, broke through the barrier, and bit Horus.

When Isis returned, she found Horus near death from the deadly poison.

She cried out to Thoth for help. Upon arriving, Thoth was astonished that Isis had not yet realized her own powers.

He assured her that she could wield the power of the sun.

When Isis spoke the magical incantation, the solar barque appeared in the sky and stopped above them.

Its light shone down upon Horus, and darkness fell over the land.

Thoth told Isis that this darkness would last until Horus was healed.

Isis realized that if Horus died, the current world would end, and a new world ruled by Set—one of darkness and evil—would begin.

The powerful sun spell purged the poison from Horus’s body, and he was resurrected.

The Eye of Horus and Egyptian Fractions

What follows is the beginning of the battle between Horus and Set, though the detailed account will be omitted here.

Instead, let us focus on a story related to mathematics—the story of “The Eye of Horus.”

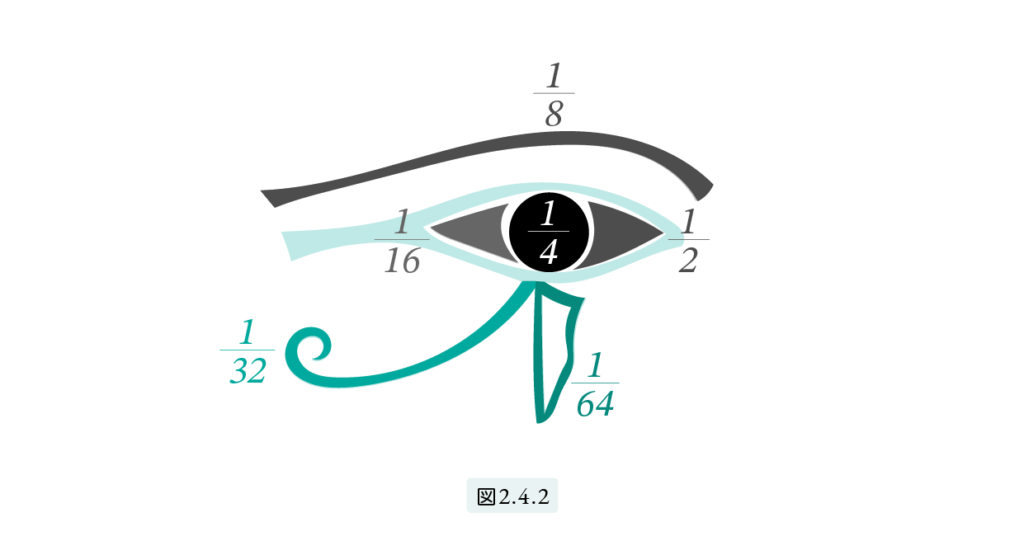

During their fierce battle, Set gouged out one of Horus’s eyes and tore it into six parts, as shown in Figure 2.4.2.

Each of these six parts represents the following fractions:

1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32, 1/64 (1)

The ancient Egyptians used special types of fractions known as Egyptian fractions. Among them, the set of fractions listed in (1) is referred to as binary fractions.

When all the fractions in (1) are added together, we get:

1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 = 63/64 (2)

This sum is just slightly less than 1. Some jokingly say that “the Eye of Horus was slightly incomplete.”

However, expressing a value less than 1 with a precision of 1/64 is accurate enough for most practical uses.

For comparison, the smallest unit of length used in everyday life today is the millimeter, and 1/64 millimeter is approximately 15 microns.

Isis’s Strategy and the Secret Name of Ra

After Set was cast out and Horus inherited the throne, justice and order returned to the world. Isis, admired as a woman of great charm and dignity, became widely celebrated. Yet, ironically, this admiration led her to grow weary of mortal life. She longed to ascend to the heavens, to live among the gods as a star—and if possible, to become the queen of all goddesses.

In ancient Egypt, each god had many names, but their true names were kept secret. Isis devised a plan to seize the power of the sun god Ra by learning his true, secret name. Everything in the world was created by Ra, and nothing he created could harm him. However, Isis noticed that Ra, now old and drooling from his mouth, produced something not of his creation: his own saliva.

Secretly collecting Ra’s drool, Isis mixed it with dust to form a poisonous serpent. She placed the serpent on the path where Ra walked each day. The next morning, the serpent bit Ra as he passed, and he writhed in agony. Many gods rushed to his aid, but none could help.

Isis appeared with an innocent face and asked what had happened. Approaching Ra, she said, “Could anything you created truly harm you?” She then offered her help, declaring, “Tell me your name. With my magic, I can summon back your life.”

Ra began to list names, one after another—but none were the secret name. Isis insisted, “Without your true name, there is nothing I can do.” Finally, Ra spoke to her heart directly.

The ancient Egyptians believed that people thought not with the brain, but with the heart. Thus, “speaking from heart to heart” was considered a kind of telepathy.

Isis quickly summoned her son Horus. Then Ra spoke into both their hearts: “My name must not be revealed to anyone but you two. I give my two eyes to Horus.” Upon hearing this, Isis removed the poison from Ra’s body.

The Connection Between Horus and the Sun God: A Symbol of Rebirth

Horus was regarded as the guardian deity of the pharaoh, or even as the pharaoh himself. This myth symbolizes the strong bond between Horus, the king, and Ra, the sun god. The two eyes of Horus were considered to be the sun itself.

As mentioned earlier, when Horus was bitten by the serpent disguised as Set and was on the verge of death, the world was plunged into darkness. The death of the pharaoh meant that the world would be engulfed in darkness, collapse, and bring about the death of its people. The pharaoh bore responsibility for maintaining the order of the world.

Although the pharaoh was human and thus mortal, his true form as Horus was immortal. In all ancient civilizations (including Japan), the sun god is associated with rebirth—dying at night and rising again in the morning, or dying in winter and reviving in spring. For this reason, the sun takes on various forms and plays different roles.

Understanding this perspective may help make sense of the apparent contradictions within Egyptian mythology.

The Book of the Dead and Anubis

To better understand the ancient Egyptians’ view of life and death, let us add one more story. Set’s wife was his sister Nephthys. As Set was the god of the barren desert, the couple had no children. Secretly, Nephthys held feelings for another brother, Osiris. She bore a child, Anubis, by Osiris, but fearing her husband Set, she abandoned the baby in the marshes of the Nile Delta.

Isis, with her divine powers, knew everything. She searched the marshes accompanied by a jackal and eventually found the infant Anubis. From that point on, Anubis became the adopted son of Isis and aided her. It was Anubis who stitched together the dismembered body of Osiris that Isis had collected, embalmed him, and helped Isis bring him back to life. Since Osiris was the first mummy and his embalming was the first funeral ritual, Anubis came to be regarded as the god of mummification and funerary rites.

Anubis is the jackal-headed god. The jackal is a canid that lives in the western desert and feeds on carrion. Like in Japan, in Egypt the west was considered the land of the dead. Giza, where the Great Pyramid stands, lies on the west bank of the Nile and was considered the domain of Anubis, god of the dead.

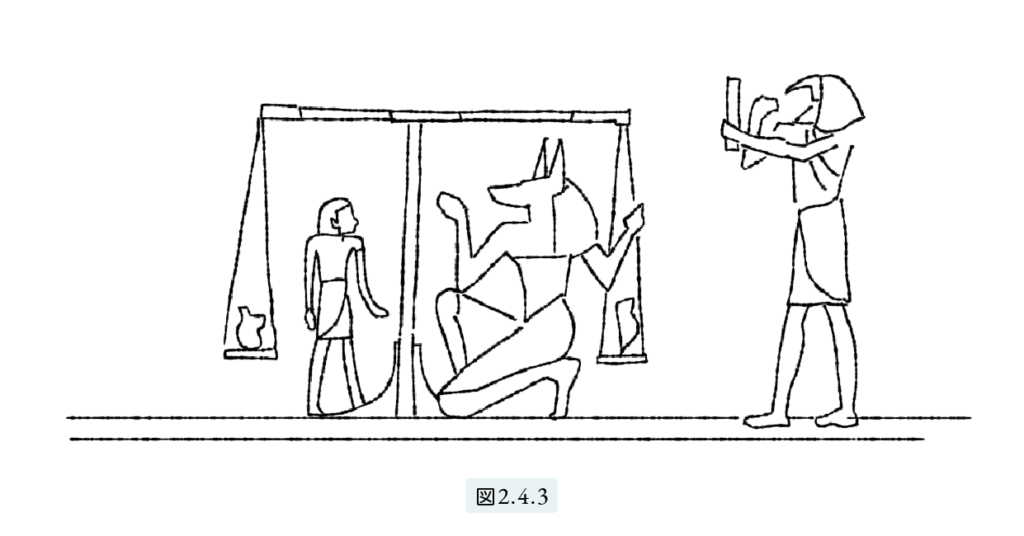

For common people, concerns about the afterlife were of great importance. When a person died, they were believed to go to the underworld ruled by Osiris. There stood a great scale representing absolute truth and balance—this scale itself symbolized the goddess Ma’at. On one side of the scale was placed the heart of the deceased, and on the other, either a small figure of Ma’at or an ostrich feather, the symbol of Ma’at. If the scale balanced, the deceased was granted eternal life; if not, their heart would be devoured by a monster.

In the scene depicted in Figure 2.4.3, Anubis is weighing the heart, and the scribe Thoth is recording the results.

The Osiris myth is said to have transformed from a folk tale into a royal myth. However, it seems that the ones who listened to this story most earnestly were the common people. Isis devoted herself to the desperate search for her husband’s body and resisted Set’s temptations. She also protected her son from Set’s evil grasp and secured his right to inherit the throne. Isis’s behavior—both as a faithful wife and as a devoted mother—likely resonated deeply with the public. The popularity of Isis endured throughout the entirety of ancient Egyptian history, continuing even into the Roman period.

It is often said that the Osiris myth was created to enhance Osiris’s authority as a king. As a result, however, it also served to associate the pharaoh with Horus, thereby elevating the divine status of the pharaoh himself.

Animal Worship and Ancient Egypt

In Egyptian mythology, there are many instances of animal worship—monkeys, birds, dogs, and more. Europeans once viewed this as a primitive and backward form of religion. This perspective stemmed from the conflict between Christianity and non-Christian beliefs, but in recent times, such views have come under reconsideration.

There are traces of animal worship even in Japanese folktales. Let’s take a look at the story of Urashima Taro. Interestingly, this tale contains no proper names. “Urashima Taro” simply means “the eldest son living on the far side of the island,” and “Otohime” originally meant “younger princess” (as opposed to the “older princess”). The father of Otohime is a dragon god, which implies he is a serpent deity. Why is it the younger princess and not the older one? Because the elder sister became so devoted to Buddhism that she transformed into a man—an example of male-dominant ideology.

Taro is chosen by Otohime and enters the celestial realm (a kind of “reverse Cinderella” story, which is common in Japanese folklore). The tamatebako—a treasure box—is a private item used to hold a woman’s cosmetics, and the word tama means “beautiful.” Otohime was a turtle in disguise. One day, while she was resting in her turtle form inside the box, Taro discovered her. Enraged, Otohime sent him back to the mortal world.

As this story shows, even in Japan, people once kept their real names a secret—because revealing a name meant exposing oneself to curses. Women, in particular, would reveal their names only to their husbands. This is why proper names rarely appear in Japanese poetry like waka. It wasn’t necessarily because women held a lower social status, as is commonly believed. Even today, Japanese people tend to refer to others using titles—like shacho (president), sensei (teacher), oneesan (miss), or okaasan (mother)—rather than proper names.

The Divinity of the Pharaoh and the Pyramids

The widespread belief in the Osiris myth and the cult of Osiris began in earnest after the Middle Kingdom period. During the Old Kingdom—the so-called Pyramid Age—Osiris had not yet become a central deity. Let’s go back to the beginning of the Old Kingdom and revisit the role of mythology. In ancient societies, the larger a group’s population, the greater its power. Creation myths were not just for the royal family; they served to gather believers from the entire region. To win battles, group unity was essential, and for that, the charisma of the king needed to be strengthened. With the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza, the king’s charisma reached its peak. At the same time, mythology began to change. Numerous gods behaved like humans—marrying, fighting, and feuding.

Kings and priests began conducting religious rituals within walled-off, isolated sacred spaces. By the Fifth Dynasty, religious texts known as the Pyramid Texts began appearing inside burial chambers of the pyramids. These writings, which seem to be excerpts from older religious texts, centered on the theme of the pharaoh’s eternal life. They were not intended for public dissemination but rather served as personal spells expressing the king’s wish to ascend to heaven and become a god. The pharaoh himself began to believe that he had to recite such spells to justify his worthiness of deification. Thus, a shift occurred in belief: “the living pharaoh is not a god incarnate; he becomes a god after death.”

As the divine status of the pharaoh weakened, focus shifted away from the pyramid itself to the funerary complexes surrounding it and the rituals performed there. Consequently, the construction of the pyramids became increasingly crude over time.

Summary

In this section, we explored the beliefs and views on life and death held by the ancient Egyptians, focusing on the Osiris myth. By gaining a clearer understanding of what the pyramids represented, we will gradually uncover the numerical mysteries hidden within them.