The Pyramid as a Symbol of Sacred Order (Maat)

Many books on the history of mathematics attribute the origin of mathematics to the development of agriculture and commerce. While these are certainly major reasons, it seems that other motivations also existed—such as astrology (astronomy) and divination (numerology). Some books on the history of the Orient simply assert, without explanation, that “Oriental astrology was entirely different from the science of astronomy.” However, it is likely that ancient astrology was not so fundamentally different from astronomy. People observed the night sky and the sun daily, linking celestial events to phenomena occurring on Earth. As days passed, the sun’s elevation would change: when the sun was directly overhead, summer would come; when lower, it signaled winter. Additionally, the Nile River began its annual flooding at a predictable time.

People may have believed that the entire world was governed by an orderly system—and that the underlying principle of that order was number. The pyramid, with its square base and four triangular faces, may have been intended as a symbol of this sacred order, known as Maat. To understand this, let us explore how the pyramid came to be built in its iconic form.

Imhotep and the Step Pyramid: The Establishment of Kingship and the Divine King Ideology

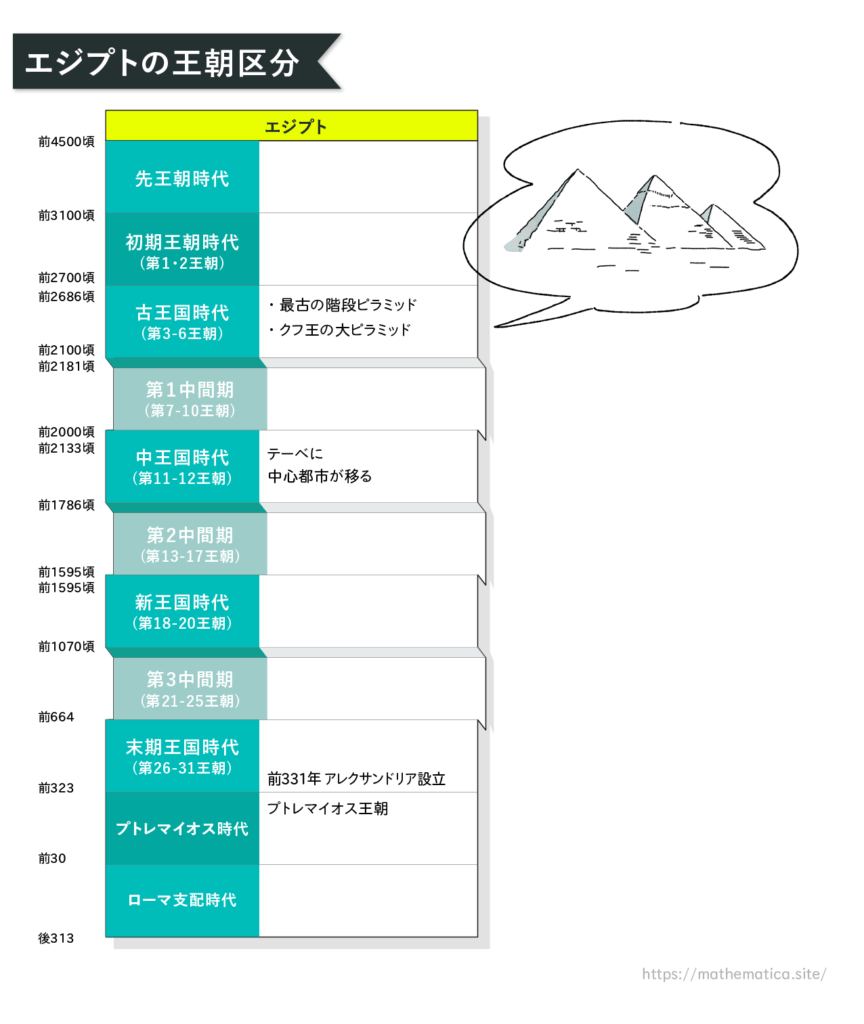

By the time of the Old Kingdom, the kings began building elaborate tombs. During the Early Dynastic Period (1st and 2nd Dynasties), royal tombs were modest structures known as mastabas, rectangular buildings made of sun-dried bricks. The first true pyramid was constructed during the 3rd Dynasty by King Djoser. This massive 60-meter step pyramid was part of a grand funerary complex that included temples and courtyards. The architect behind this complex was Imhotep, a vizier and high priest of the religious city Heliopolis. He laid the foundations of mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, and throughout Egypt’s long history, he came to be revered and worshipped as a great sage. In the New Kingdom period, he was deified and associated with the god Thoth, becoming the patron deity of scribes. Later, during the Hellenistic period, the Greeks identified Imhotep with their own god of medicine, Asclepius.

The step pyramid designed by Imhotep was the first monumental structure made entirely of stone. It symbolized the realization of a fully developed kingship and the establishment of a powerful centralized state. The pyramid, built with stone that seemed to promise eternal durability, served as a public declaration of the ideology that “the king is a god.” Imhotep’s design set the standard for future pyramids, and he has since been remembered as the inventor of the pyramid.

As the high priest of Heliopolis, Imhotep was deeply familiar with the doctrines of solar worship. Various creation myths, including sun worship, gradually merged over time, and by Imhotep’s era, Heliopolis had become the most authoritative religious center in Egypt. Imhotep linked this religious authority with the ideology of divine kingship. According to the creation myth, the Benben bird was the first to land on the primordial hill (the symbolic pyramid). This bird was also a phoenix and identified with Thoth—the god of wisdom who taught writing and mathematics to humans.

The Pyramids of Giza: Supreme Architecture and a Symbol of Solar Worship

By the time of the 4th Dynasty, true pyramids in the form of square-based pyramidal structures began to be constructed. The first king of the 4th Dynasty, Sneferu, built as many as three pyramids in succession. Why he constructed three pyramids, and in what order, has been the subject of much debate among historians. This topic will be revisited in detail in a later chapter.

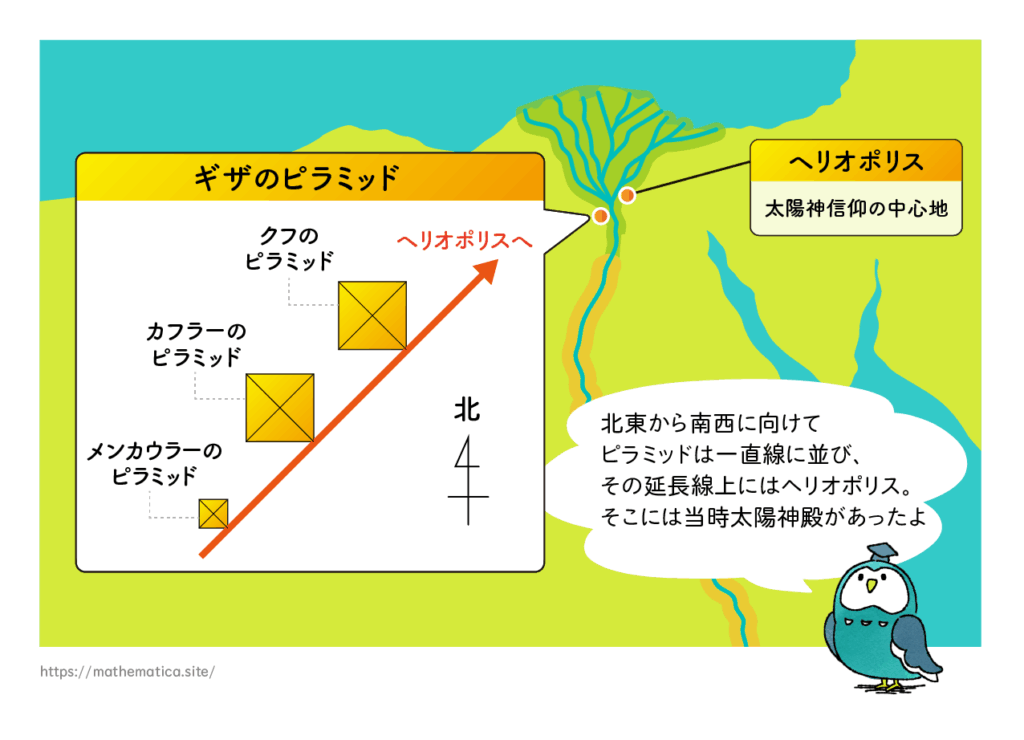

Sneferu’s successors—Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure—each built a pyramid complex at Giza, which collectively represent the largest and most perfected pyramids of all time. These three pyramids are aligned in a straight line from northeast to southwest, and this alignment points toward Heliopolis, where a solar temple once stood. It is evident that these pyramids were built according to the doctrines of solar worship established by Imhotep, the architect of the step pyramid and a high priest of Heliopolis.

Decline in Pyramid Construction During the 5th and 6th Dynasties

During the 5th Dynasty, pyramid complexes continued to be built, but the pyramids themselves became smaller in scale and more crudely constructed. The 6th Dynasty marks the decline of the Old Kingdom; the nation weakened, and the pyramids became increasingly modest and fragile. This period coincided with a climatic shift toward aridity across North Africa. As the volume of the Nile decreased, famine is believed to have struck the Nile Valley. When the Pharaoh could no longer control nature, his divine authority came into question, and royal power began to collapse.

Society descended into disorder, giving rise to a form of pessimistic literature known as The Admonitions of Ipuwer. This text paints a grim picture of the times:

“Men’s hearts are violent, disaster is throughout the land, blood is everywhere.”

“People hide in the shadows of thickets, attacking travelers and stealing their belongings. The traveler is beaten with a stick and dies…”

Pyramids continued to be built sporadically even after the Middle Kingdom, but the use of durable stone materials decreased, and sun-dried bricks became more common. As a result, many later pyramids collapsed easily, and what remains today is often just heaps of rubble.

Ancient Egyptian Views on the Afterlife and the Cosmos

Let us now explore the ancient Egyptians’ views on the afterlife. As mentioned in the previous section, the widespread belief in Osiris developed after the Middle Kingdom. By the time of the Middle Kingdom, more historical records became available, offering insights into various aspects of their beliefs and society. For the Old Kingdom period, valuable information is derived from the Pyramid Texts, which began appearing around the 5th Dynasty. These texts also shed light on the era of King Khufu.

The step pyramid designed by Imhotep is thought to have been a staircase for the pharaoh, regarded as a divine being, to ascend to the heavens and join the gods after death. This interpretation is supported by the Pyramid Texts and widely accepted by historians. The pyramids at Giza likewise served as devices to facilitate the pharaoh’s ascension. Creation myths formed the ideological foundation for pyramid construction.

At some point, the Osiris myth was incorporated into the concept of divine kingship. When a pharaoh died, he was believed to descend to the underworld and become one with Osiris, the king of the afterlife. His successor, the new king, would then rule the earthly realm as Horus, the son of Osiris. Through the development of the scribal bureaucracy and the priesthood, belief in the “divine king” spread among the people. This gave them a sense of reassurance: the afterlife was protected by the former king as Osiris, while the present world was safeguarded by the reigning king as the incarnation of Horus.

The Democratization of the Afterlife and the Eye of Ma’at as Seen in the Osiris Myth

In the early stages of the Osiris myth, it was likely believed that only the pharaoh could live in the underworld as the god Osiris after death. However, as stories of the afterlife began to take more concrete form, the belief evolved: everyone, not just royalty, could journey to the land of the dead, where their deeds in life would be judged by the goddess Ma’at. If deemed worthy, they would be granted life in the afterworld. This concept is referred to as the “democratization of the afterlife.”

Ma’at, the goddess of truth, justice, and cosmic order, may have been the true moral compass for all Egyptians—playing a key role in sustaining a stable and orderly society. In modern Japan, many people identify as non-religious and may have difficulty understanding the role of religion in shaping values. Imagine walking down an empty road at night and finding a large sum of money. In many religious cultures, it is assumed that in a world without divine oversight, anyone might pocket the money without hesitation. In the Admonitions of Ipuwer, the despair and chaos described stem from the belief that the gods had abandoned the world.

Eyes frequently appear in Egyptian mythology and wall paintings. Could these ever-watchful eyes be the eyes of Ma’at herself, symbolizing the constant presence of divine judgment?

The Spread of Ma’at Worship as Seen Through Epitaphs

In Egyptian society, even officials and pharaohs believed in the goddess Ma’at. Judges were also considered priests of Ma’at, so people could rely on them with peace of mind. This trust in priests and officials was not necessarily because they were pure and incorruptible, but because they themselves believed in Ma’at. Kings and nobles alike were also devoted to Ma’at. It was common to find epitaphs on tombs inscribed with phrases like:

“I spoke Ma’at, I acted Ma’at.”

There were also mummies in Japan. Revered monks would gradually reduce their food intake to eliminate fat from their bodies. This process is called mokujiki-gyō (“tree-eating practice”). When their bodies were sufficiently dehydrated and depleted of fat, they would enter a stone chamber underground and become a mummy through a practice called nyūjō, or “entering stillness.” These self-mummified monks are referred to as sokushinbutsu, meaning “living Buddhas,” symbolizing their transformation into a Buddha in body and spirit.

Why would these monks choose to become mummies? One reason might be to pray as a Buddha so that the common people would not suffer from famine or plague. While that may have been true, it’s also likely that they wished to reach paradise themselves and join the Buddhas in the afterlife. The public, deeply moved by such noble acts, surely prayed to these sokushinbutsu—but ultimately, those prayers may have been for their own personal happiness.

Religious and Political Differences Between Japan and Egypt

In Japan, there are structures similar to the pyramids, such as the imperial tombs (kofun) and the Great Buddha statues. The construction of the Great Buddha at Tōdai-ji in Nara was also a national project. To fund the enormous construction costs, the government enlisted the help of En no Ozunu, a popular ascetic at the time, to collect donations from all over the country. Those without money contributed their labor, and women donated their long hair, which was used to make strong ropes capable of lifting massive timbers. People worked together in hopes of creating a society free from epidemics and disasters—in other words, a world where they could live in peace and happiness. But why was it necessary to build something so colossal? Compared to the power of the individual, the forces of nature were overwhelming. To face such threats, perhaps a Buddha of equally immense power was needed.

There is a key difference between Japan and Egypt. In Japan, the imperial family—the object of religious reverence—became separated from secular power, which came to be held by the warrior class (samurai). Later, Buddhism, a new religion, was introduced and eventually turned the myths that had formed the religious foundation of the imperial household into mere fairy tales. In contrast, in Egypt, religious authority and political power were always unified. However, it seems that the absolute divinity of the pharaoh began to waver gradually after the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Perhaps this reflected a shift in religious consciousness.

Let us also consider the practice of junshi—ritual suicide following the death of a lord. In Japan, human bones interpreted as evidence of junshi have been found in ancient kofun tombs. Similarly, in Egypt, remains thought to be from junshi have been discovered in royal tombs from the Early Dynastic Period. However, nothing of the sort has been found from the Pyramid Age onward, suggesting that the practice had ceased. From the modern perspective, junshi may seem cruel and horrifying, but it is possible that some people willingly chose to die. They may have believed that by dying with their king, they would live eternally in the afterlife as a servant of the divine monarch. During the Early Dynastic Period, frequent warfare made death a daily reality, but by the time of the kofun period in Japan, warfare had subsided, and attitudes toward life and death likely changed.

The Sacred Purpose and Religious System Behind the Construction of Khufu’s Great Pyramid

How was the Great Pyramid of Khufu constructed?

Most likely, the priests conveyed the following message to the people:

God created this world and established the cosmic order (Ma’at), appointing the Pharaoh as His own incarnation to uphold it.

The fact that the Nile River rises regularly and brings blessings to all is undeniable proof that the Pharaoh is fulfilling the divine role.

When the king completes his role in this world, he ascends to the heavens after death and becomes one of the stars, watching over the people.

The Pharaoh was a god, and the pyramid was not merely a tomb for a single king.

Rather, it was a symbol of the Pharaoh’s divine power—the power to maintain Ma’at (cosmic order)—and served as a temple safeguarding the peace and prosperity of the entire nation.

It is likely that King Sneferu built as many as three pyramids because the pyramid was not simply a tomb or a stairway to the heavens, but rather something akin to the Great Buddha of Japan—a monument to protect the stability of the state.

Conclusion

The greatest mystery of the Great Pyramid is how such an enormous stone structure could have been built some 4,500 years ago. Common explanations include the absolute power and wealth of the pharaoh, the architectural and managerial expertise of the scribes, and the advanced techniques of stone construction.

However, perhaps even more important was the passion and determination of the Egyptian people to accomplish such a monumental national project. Without the unity and cooperation of the entire population, such a feat would not have been possible.

There is an inscription that describes a scene in which a massive statue—not a pyramid—was moved by the combined efforts of many people:

— The young supported the old, and beside the weak stood the strong. Their spirits were stirred, their arms surged with power, and each one displayed the strength of a thousand men. —

In Chapter 2, we have explored the environment in which ancient Egyptians lived, the role of the pharaoh, their mythology, and beliefs about the afterlife. We have also come to understand that the pyramid was not merely a tomb for a king but a symbol of Ma’at (cosmic order) and a temple that safeguarded peace and prosperity for all people.

In Chapter 3, we will now turn to the mathematical capabilities of the ancient Egyptians.