The Worldview of Ancient Egypt as Seen Through Mythology

How Did Ancient People Perceive the World?

To understand the worldview, cosmology, and ethics of ancient people, mythology serves as an invaluable reference. Why, for example, are pyramids shaped like square-based pyramids? In contrast, the tombs of ancient Japanese emperors were circular or keyhole-shaped mounds, quickly overgrown with trees and blending into the natural landscape, making it difficult to distinguish them from hills. This may reflect fundamental differences in how ancient Egypt and Japan perceived nature.

Mathematics is generally thought to have emerged from practical needs such as taxation and trade, but another major driving force was numerology. Ancient people believed that numbers, like words, possessed magical powers. Numerology gave rise to fortune-telling, and fortune-telling, in turn, emerged from astronomical observation.

In modern times, we no longer feel that words or numbers carry mystical power. However, ignoring this may cause us to misinterpret the mindset of ancient people. If we consider ancient mythology as analogous to modern science fiction or historical novels, we may gain a deeper appreciation for the richness of their imagination.

The Formation of Tribes and Provinces in Ancient Egypt

Migration to the Nile Valley and the Rise of Totemic Society

Around 9,000 years ago, people from various regions began gradually gathering in the Nile Valley in search of water. Each group had its own guardian deity, often represented by animals such as birds or crocodiles, or natural phenomena. These guardian spirits are known as totems. As groups merged, they formed tribes, and as tribes united, they formed larger administrative units or provinces (nomes). The guardian deity of a tribe’s leader would eventually become the guardian of the entire province, and the leader himself took on a spiritual role as a priest imbued with the divine power of the totem, gaining charismatic authority.

In the ancient world, war was seen as a conflict between the gods of rival tribes. Typically, the defeated god would be subjugated or erased by the victorious one. However, in Egypt, such phenomena did not occur. Instead, the number of gods continued to grow. Major deities of one tribe were amalgamated with those of others to form composite gods—a process called syncretism. Rather than one name disappearing, both names were often preserved. For example, the gods Ra and Atum were combined into Ra-Atum.

Over time, a single deity could possess multiple names and forms. For instance, the god Thoth was depicted both as an ibis and a baboon. As a result, divine genealogies became highly complex, often containing contradictions. In one region, a pair of deities might be described as parent and child, while in another, their roles might be reversed or rewritten as grandparent and grandchild.

The Coexistence of Social Structure and Myth: The Relationship Between Egyptian Society and Religion

In most mythologies, the system of deities and stories becomes more organized and coherent over time. However, Egyptian mythology allowed contradictory myths to coexist peacefully, without demanding logical consistency. This appears to reflect the structure of Egyptian society itself.

In later Roman times, the ruling Romans saw the Egyptian people merely as subjects from whom taxes could be extracted, and thus imposed strict legal and administrative control. In contrast, during the dynastic period of Egypt, the king was considered a god by the people, and therefore had to respect the religious beliefs of the populace. In other words, Egypt was a society that valued regional customs and traditions, and allowed for differences to exist.

Every mythology includes a creation myth about the birth of the universe. In Egypt, there were four major centers of worship, each with its own creation myth. Here, we will focus on the creation myth from Heliopolis, a religious city located near Giza and closely associated with the construction of the pyramids.

The Creation Myth of Heliopolis

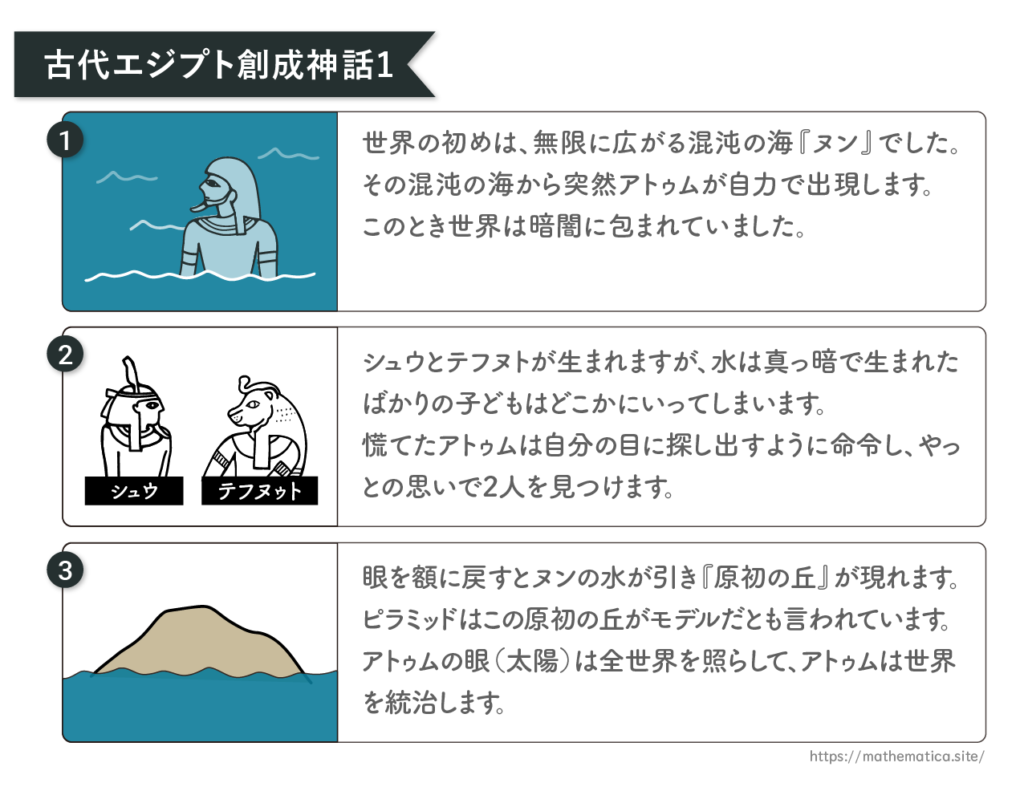

Creation Myth I: The Primordial Mound

Creation Myth I: The Primordial Mound

In the beginning of the world, there was an infinite, chaotic ocean. The ancient Egyptians likely envisioned this as the endless surface of water left behind after the annual flooding of the Nile. This cosmic ocean was called Nun. Nun was the source of all creative power and appears across all Egyptian creation myths—sometimes even regarded as a god.

Nun remained stagnant for a long time. In the myth of Heliopolis, the god Atum suddenly came into being by his own will within this watery chaos. With his emergence, finite space appeared, and time began to move. In this dark and formless sea, Atum spat to create his son Shu, and vomited to bring forth his daughter Tefnut. But the surrounding waters were still in darkness, and the newborn children became lost.

Atum panicked and commanded his eye to find them. At this point, Atum had only one eye—an eye that possessed a will of its own and could move freely. After a difficult search, the eye finally found the two children and returned them to Atum. But upon returning, it discovered that Atum already had a new, brighter eye beside him. Atum, feeling remorse, placed the original eye on his forehead.

With that, the waters of Nun receded, space was formed, and Atum appeared above the water’s surface. This emergence is called the Primordial Mound. It is said that the pyramid was modeled after this sacred mound. The eye of Atum—the sun—began to illuminate the entire world, and Atum took on the role of ruler of the cosmos.

It was only after the construction of the pyramids began that myths started to be depicted in wall paintings and inscriptions. By that time, the god Atum had already come to be identified with the sun god Ra. Various traditions exist—for instance, in some accounts, Atum’s right eye is the sun and his left eye is the moon. In this context, we will regard Atum as being synonymous with Ra, and from here onward, refer to him as Ra.

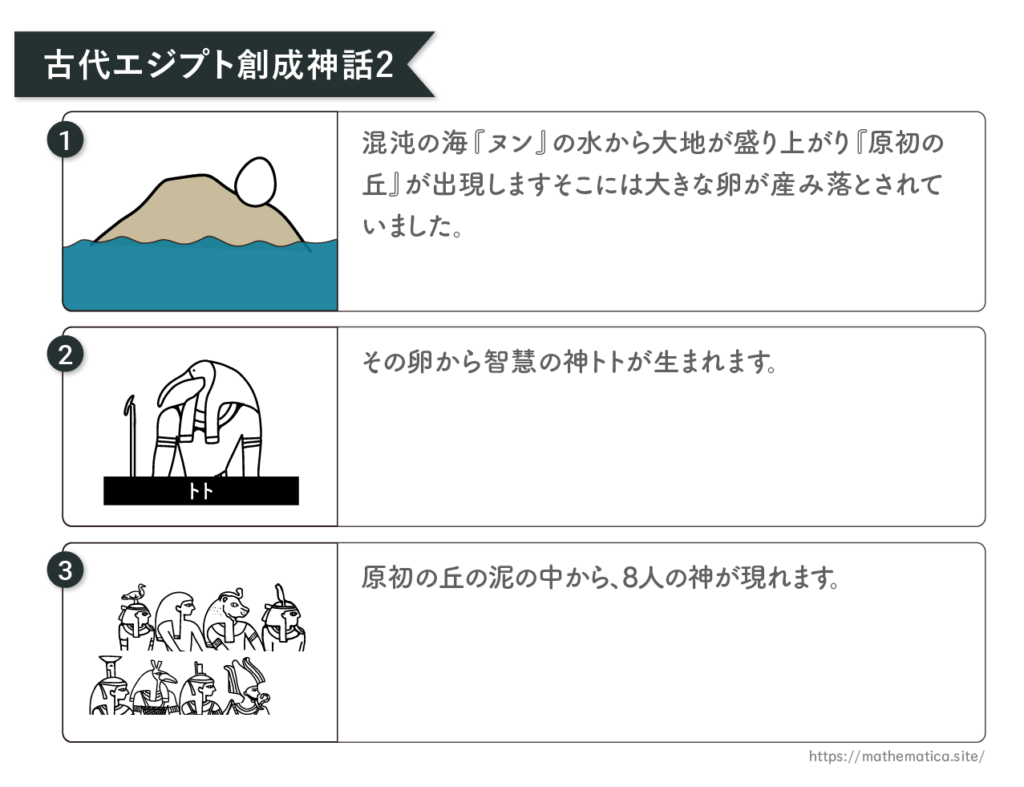

Creation Myth 2: The Primeval Hill and the Birth of Thoth

Another creation myth was passed down in Heliopolis in Middle Egypt. In this myth as well, the chaotic waters of Nun give rise to a mound of earth known as the Primeval Hill. Nun possessed the power to give birth to all things, and on this Primeval Hill, a great egg was laid. From this egg was born Thoth, the god of wisdom.

Thoth emerged as a radiant bird of fire, who would later become known as the Phoenix.

From the mud of the Primeval Hill, eight deities appeared. Among them, four were male gods with the form of frogs, and four were female goddesses in the form of snakes. This likely reflects the scene after the Nile floodwaters receded, when countless frogs and snakes would appear in the marshes. The Nile was truly the source of life.

The four male frogs and four female snakes married each other and gave birth to many other gods. Incidentally, in Japan, the counter for gods is usually “柱 (hashira)”, not “people” or “animals,” but in this context, using “people” or “creatures” makes more sense in English—for example, referring to “four frog gods” rather than “four divine pillars of frogs.”

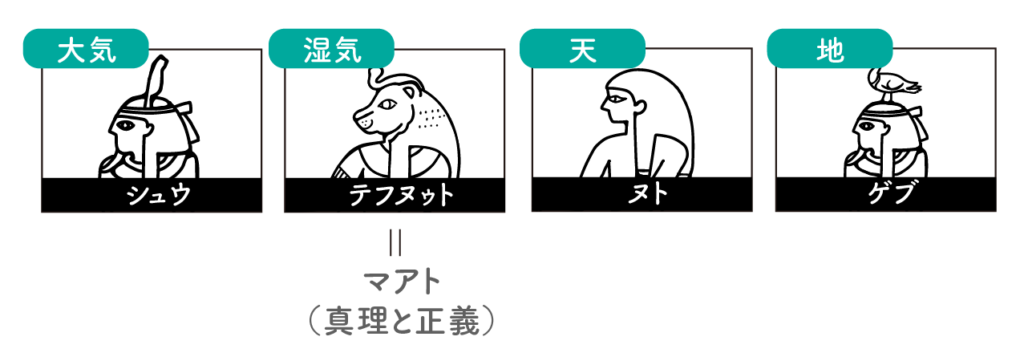

The Children of Ra: The Birth of Nut and Geb

After the creation of the primeval hill, the sun god Ra (formerly Atum) gave birth to two children: Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture. Shu and Tefnut then gave birth to Nut, the goddess of the sky, and Geb, the god of the earth.

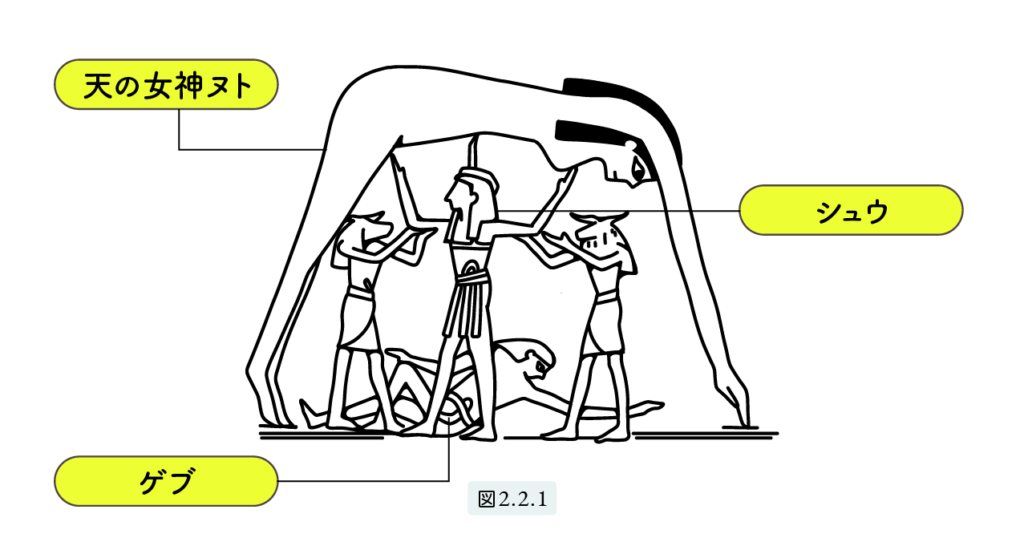

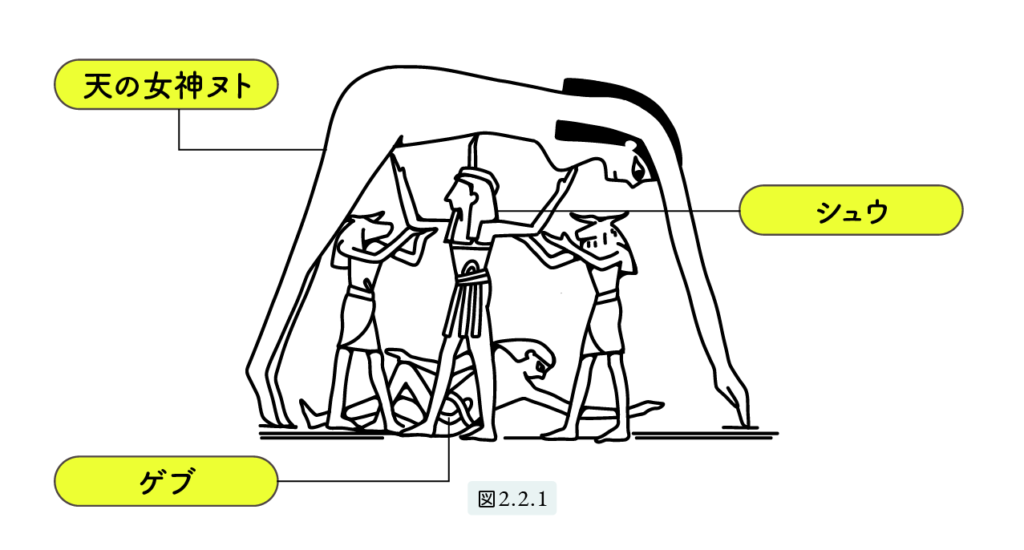

In ancient Egyptian cosmology, Nut and Geb were depicted in a striking and symbolic way—Geb lay on the ground, his body representing the earth, while Nut arched above him, her body forming the heavens. The space between them, filled with air, was Shu himself, who held Nut up and kept the sky and earth apart.

It was believed that every evening, the sun (Ra) would enter Nut’s mouth, travel through her body during the night, and be reborn at dawn from her womb—thus continuing the cycle of day and night. This myth reflects the Egyptians’ view of the cosmos as an ordered, cyclical process maintained by divine beings.

Thoth’s Wife and the Separation of Nut and Geb

Thoth’s wife is Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice. Since Ma’at is often identified with Tefnut, this makes her a child of Ra as well.

Originally, Nut (the sky goddess) and Geb (the earth god) were united as one. However, their father Shu, the god of air, separated them by force.

Figure 2.2.1 Egyptian Cosmology:

Nut, the sky goddess, stretches across the heavens, supported by her hands and feet.

In the center, Shu, representing the atmosphere, holds her up.

Beneath them lies Geb, the earth god, stretched out along the ground.

This scene illustrates the ancient Egyptians’ cosmic order—earth below, sky above, and the air in between—sustained by divine intervention.

The Perfect 360-Day Calendar and the Addition of Five Days

Why Five Days Were Added to the 360-Day Year

In the world created by Ra, the year was a perfectly ordered 360 days, which brought great clarity and harmony. But mythology explains why five additional days were added.

Ra, though the grandfather of Nut (the sky) and Geb (the earth), was a jealous deity. He disliked that Nut and Geb were always together, so he ordered Shu, the god of air and their father, to separate them.

Separated and yearning to reunite, Nut and Geb turned to Thoth, the god of wisdom, for help. Thoth challenged the moon god, who governed time, to a game of chess and won 1/72 of each of the 360 days—equivalent to five days in total.

Thanks to this victory, these five epagomenal days were added to the calendar, making a full year 365 days. During these five special days, Nut and Geb were permitted to be together, and Nut gave birth to five children: Osiris, Set, Isis, Nephthys, and Hathor.

In some traditions, Horus replaces Hathor among the five children, or Hathor is instead considered the daughter of Nut and Ra.

This myth shows that the ancient Egyptians understood the solar year as 365 days, and that they tracked the calendar based on lunar phases.

Hathor and Sekhmet: The Daughter of the Sun God and the Goddess of Destruction

The Birth of Humanity, the Rule of Ra, and the Tale of Hathor and Sekhmet

Humans were born, and Ra, along with the other gods, ruled the world. At this time, Ra was still young and vigorous. The power of Maat, the goddess of divine order, permeated every corner of the world, ensuring a firm and orderly governance. Ra led a daily life of strict routine. Every morning he would rise, apply his makeup, eat the meals brought by the gods of the stars, and then depart from the “Temple of Benben” in Heliopolis. Accompanied by gods like Shu, he would travel along the Nile River, inspecting the twelve provinces of the kingdom. This era, when gods and humans lived together in harmony, is known as the “Golden Age.”

The sun god Ra was not merely a deity of blessings for humanity—he also demanded harsh labor, much like the scorching sun of the desert. Humans would sometimes rebel. When a rebellion occurred, Ra would erupt in rage and send forth his daughter Hathor. In her fury, Hathor transformed into the lioness goddess Sekhmet. Sekhmet embodied Ra’s hatred, cruelty, and destructive will. Once she tasted blood, she could not be stopped.

Ra had never intended for the total annihilation of humankind. But the massacre and brutality became so horrifying that the other gods turned to Thoth for help. Thoth dyed a vast quantity of beer red with strawberries and placed it in large jars along Sekhmet’s path. The next morning, bloodthirsty Sekhmet found the jars, mistook them for blood, drank them eagerly, and fell into a drunken sleep.

When she regained consciousness, the savage lioness Sekhmet had returned to her former self—gentle Hathor.

The Sun and Moon Myth: The Eyes of Ra and Atum

In the story mentioned at the beginning of this section, the sun god Ra is described as the eye of Atum. In some versions, Atum’s right eye is the sun (Ra), and the left eye is the moon. In these myths, Hathor is said to be the daughter of Ra, but in other versions, she is described as the Eye of Ra itself. Egyptian gods often change names, forms, and roles depending on the context. While it may seem strange, it suggests that ancient mythology and religious beliefs cannot be fully grasped using modern ways of thinking.

Another myth about the Eye of Ra tells this story: One day, the Eye of Ra runs away again. In this version, the Eye is Ra’s daughter Tefnut (also identified with Ma’at). Ra asks Thoth to search for her. Thoth eventually finds Ma’at in a distant land, and as a result, he marries her. As a reward, Ra grants Thoth the right to create the moon and entrusts him with the rule of the night sky as Ra’s representative. It is believed that Thoth absorbed local lunar gods into himself through this act. Because of this, Thoth was said to gain the power to control the calendar—that is, the days and months.

The Conflict Between Horus and Set: The Turmoil of Succession in Ancient Egypt

Ra Grows Old and Transfers the Throne

As Ra grew old, he passed the divine kingship to Shu. Afterward, Shu’s son Geb seized the throne from his father and became the third ruler. Geb’s reign was a time of stability, and the royal throne on earth came to be called “the Seat of Geb.” After a long reign, Geb decided to abdicate and planned to divide the realm—Lower Egypt to Horus and Upper Egypt to Set.

However, this issue of succession led to great confusion and conflict.

Horus and Set clashed over the inheritance, and the gods debated who had the legitimate right to rule. Ra supported Set, but he was seen as senile, and none of the other gods were willing to follow his judgment. Disillusioned, Ra decided to leave the earth and ascend to the heavens. It is said that the posture shown in Figure 2.2.1—with Nut, the sky goddess, arching over the earth—represents the moment when Ra asked Nut to lift him up into the sky.

×

On Nut’s back rests the Solar Barque, with Ra at its center, having transformed into a scarab beetle pushing a round orb. The scarab, also known as the dung beetle, received its name from its behavior of rolling balls of dung across the ground and into its nest. Because it seemed to be reborn from these earthen spheres, it was worshipped as a symbol of the sun.

The struggle for the throne between Horus and Set is known as the Myth of Osiris. We will explore that in Section 4. For now, let us summarize the key points from this section.

The Primeval Mound in Creation Myths: Emergence from Chaos and the Symbolism of the Pyramid

Creation myths from various regions of Egypt commonly assert that the world began from a “primeval mound” that rose from a chaotic sea. Priests at each local cult center claimed that their temple stood upon this very primeval mound. Many historians believe that the pyramids were modeled after this primeval mound. Among the various cult centers, Heliopolis—located near Giza—was one of the oldest and most influential. The temple of Ra in Heliopolis was called the Mansion of the Benben.

The word Benben means “to rise” or “to swell,” and is said to have given rise to the word weben, meaning “to shine” or “to rise (like the sun),” thus linking it to the sun.

According to tradition, a sacred object known as the Benben Stone was enshrined in the Mansion of the Benben. The first creature said to have landed upon this stone was the Bennu bird. The Bennu bird is none other than the legendary Phoenix, and is also associated with the god Thoth. Earlier, we saw that Thoth was said to be born from an egg laid on the primeval mound. In another tradition, the Bennu bird appears atop the mound in a blaze of radiant sunlight, and from the egg it lays, Ra is born. Some versions of the myth even claim that the Bennu bird itself is Ra.

Summary

In the Primeval Age—The “Golden Age” When Gods and Humans Lived Together

In the primeval age, known as the “Golden Age” when gods and humans lived side by side, humans still lived primitive lives. They were still savage, sometimes even cannibalistic, and would occasionally incur the wrath of the gods. However, the gods taught humans various forms of knowledge and gradually guided them toward civilization.

Among the many theories surrounding the “Secrets of the Pyramids” is the idea of a “super ancient civilization.” This theory may have its roots in the myths of this “Golden Age.” Egyptian mythology features gods with the heads of animals, such as the ibis or the baboon. This is reminiscent of modern science fiction—like Star Wars—which often features extraterrestrial beings with unusual appearances. It feels as though ancient myths have been reimagined in modern times as stories of outer space.

Many gods have appeared in these narratives, but it is especially important to remember Thoth and Ma’at. Thoth is the god of wisdom and the inventor of writing, numerology (including mathematics and astronomy). His wife Ma’at is the goddess of truth and cosmic order. These two deities also play important roles in the “Myth of Osiris.”