Changing Perceptions of Egyptian Civilization from a European Perspective

Our way of thinking has changed significantly over time. One of the most notable shifts in recent history is our awareness of discrimination.

In Japan, for example, a strict social hierarchy existed during the Edo period, and even in the Meiji era, society was divided between nobility and commoners.

In Europe and America, slavery remained in place until relatively recent centuries.

Attitudes toward religion, divination, and superstition have also undergone major transformations.

Likewise, our interpretation of history is heavily influenced by the prevailing values and ideas of each era.

Even names of regions—such as “Europe” and “Asia”—have referred to different geographic areas depending on the time period, whether during ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, or the modern day.

This is why historical context is essential when discussing civilizations.

The evaluation and interpretation of Egyptian civilization, too, has varied widely across different times in history.

During the Hellenistic period and the Roman era, many historians and writers portrayed King Khufu as a cruel and ruthless ruler who forced 100,000 slaves to toil for 20 years.

Even Herodotus, quoting Egyptian priests, wrote that “Khufu imposed forced labor on all the people of Egypt and drove them into a state of misery”.

It seems that even the priests of Egypt at the time shared this negative view of the king.

The notion that “the Great Pyramid was built by slaves” remained the accepted belief well into the 20th century.

This image was commonly depicted in books and films about the construction of the pyramids, showing countless slaves hauling massive stones under the whips of overseers.

However, this theory has since been largely dismissed.

Archaeological evidence shows records of beer rations and wages given to workers involved in the construction of the pyramids, suggesting that they participated willingly and were not forced into labor.

It also appears that the general population lived relatively peaceful and stable lives.

The laborers were not slaves or serfs, but rather tenant farmers.

They were affiliated with the royal household, temples, or noble estates, and took part in public works such as canal building, military service, and agriculture.

Despite these duties, their lives did not appear to be excessively harsh.

Priests taught the people that “When the pharaoh dies, he becomes a god, ascends to the heavens, and becomes a star who watches over the peace and prosperity of the land.”

The priests and scribes imposed strict moral codes upon themselves and seemingly upheld them.

Had the ruling class been corrupt or self-serving, Egyptian society would likely not have remained so stable and enduring, nor would it have been possible for the people to come together to accomplish a national project as grand as the construction of the pyramids.

Pyramid Construction and the Economic System

Some readers may wonder, “Wasn’t there anything more productive to do than build pyramids?”

However, during the time the pyramids were built, foreign contact was minimal, and Egypt existed in a relatively closed world.

There were few soldiers, and manufactured goods were not widely exported abroad.

The construction of the pyramids took place during the agricultural off-season, when the Nile flooded and farming was impossible.

In this context, employing farmers for pyramid building and paying them wages was a rational and effective economic system.

This interpretation is supported by many recent publications on the pyramids—and it seems entirely plausible.

But still, one might ask: Was that truly the only reason behind their construction?

Constructing a massive stone structure like the Great Pyramid required highly specialized skills, and acquiring such techniques would have demanded long periods of training.

It was not simply a matter of gathering farmers and putting them to work.

Transporting large stone blocks was also an extremely demanding task.

Indeed, skeletal remains found at the site suggest that the laborers endured physically grueling work.

This raises an important question:

What motivated these people to leave their home villages and dedicate themselves to such backbreaking labor?

The Nile Valley was one of the most abundantly fertile regions in the ancient world.

People were not so impoverished that they needed to take on temporary labor just to survive.

Wine and bread were not luxuries limited to the upper classes.

So why did so many willingly submit to such physically demanding labor?

Was it because they had been deeply convinced by the myths crafted by the priesthood?

And why did the tradition of building massive, perfectly shaped square pyramids come to an end?

To better understand the spiritual mindset of the time, we may need to turn our attention to the myths and religious beliefs of ancient Egypt.

Egyptian society was governed through a bureaucratic system overseen by scribes.

Statues unearthed from temples and other sites often include figures of scribes, indicating the high level of respect and reverence they received.

One of the major challenges in Egyptian agriculture was tied to the Nile itself.

When the floodwaters receded, the land was left covered in thick mud, making it nearly impossible to tell which plots belonged to whom.

To complicate matters, the course of the Nile would often shift unpredictably.

But there was no need for alarm.

The land was managed by the state.

Government officials known as “rope stretchers” conducted large-scale land surveys, reorganizing farmland across the country and assigning specific plots to each farmer.

Some older history books described ancient Egyptian society in the following way:

“Royal families and priests belonged to the privileged class. Their children received a high level of education, but knowledge of astronomy and mathematics was kept secret, hidden from the common people.”

“Officials—including scribes and priests—were agents of the king and exercised oppressive control over the people.”

“Trade was monopolized by the state, and its profits were concentrated in the hands of the king alone.”

However, these portrayals have been significantly revised in recent years.

Because commerce was state-controlled, it didn’t develop much on its own.

Agricultural products and handicrafts were collected in temples, where officials redistributed them.

After the Pyramid Age—the Old Kingdom period—the number of occupations expanded greatly.

Luxury goods such as metalwork, pottery, and jewelry began to be produced, and trade became more active, though it still remained under state control.

This raises a modern question:

Did ancient Egypt truly have no “corrupt officials” or “greedy merchants” like those often seen in Japanese period dramas?

Were all officials truly honest and all farmers kind-hearted and innocent?

Differing Views of Egypt and Greece in the Roman Era

During the Roman period and the European Renaissance, people tended to divide into two camps: “Egypt enthusiasts” and “Greece enthusiasts.”

In fact, many Romans held Egypt in high regard, and there are actually more Egyptian obelisks—the tall stone monuments with pyramid-shaped tops—in Rome today than in Egypt itself.

On the other hand, those with a strong preference for Greek culture often looked down on Egyptian civilization, sometimes criticizing Egypt lovers as “barbarian sympathizers”.

Even today, many people still view Greece as the birthplace of mathematics.

Among all its contributions, the Pythagorean Theorem has become the most iconic, and until modern times, it was widely believed—without question—that Pythagoras himself had proven it.

Johannes Kepler once remarked:

“Geometry has two great treasures: one is the Pythagorean Theorem, and the other is the Golden Ratio. The former may be compared to a treasure of ten kilograms of gold; the latter, to a magnificent jewel.”

“Geometry has two great treasures: one is the Pythagorean Theorem, and the other is the Golden Ratio. The former can be likened to ten kilograms of gold, while the latter is compared to a magnificent jewel.”

Our understanding of history today owes much to the past.

The work of Herodotus, Histories, is translated as History, but the term he used, historíai, is derived from the verb historéo, meaning “to inquire” or “to investigate.”

It is from Herodotus that we see the beginning of what we now recognize as “travel writing” or “history.” He is often referred to as the “Father of History.”

His Histories is not a mere list of factual events like a modern history textbook; rather, it is an engaging narrative, written to captivate its readers.

It includes many ancient traditions and stories passed down by word of mouth, and even contemporary events are presented with the inclusion of dialogues, much like a script for a play.

While readers might feel as though they are witnessing real-time events due to the vividness of the descriptions, it seems that these writings often contain a considerable amount of fiction.

Herodotus, as a writer, sought to communicate the facts, but ancient texts were often private works, and even if the information presented was not entirely factual, there was no one to hold the writer accountable.

Thus, it seems that ancient writings were often written with a great deal of freedom.

With the rise of Rome, many writings began to focus on Greek heroes and great figures.

These works praised Greek civilization, often more in the form of stories rather than factual accounts.

For example, the writer Plutarch, a priest of the Temple of Apollo in Greece, authored the famous Parallel Lives, which consists of biographies of Greek and Roman heroes.

From a modern perspective, these biographical works of past heroes often appear to be overly complimentary—sometimes to the point where we might wonder, “Were such people really like this?”

In the 18th century, Europe’s fascination with Greece surged, and the famous philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau began…

Among the many works written about Greece and Rome, few are as engaging and insightful as the writings of Plutarch.

Writers of the time—including Herodotus—did not regard the Great Pyramid with any sense of mystery or awe.

On the contrary, they seemed to wonder why something so massive and extravagant had been built for the sake of a single king.

The 3-4-5 Right Triangle and Its Widespread Use

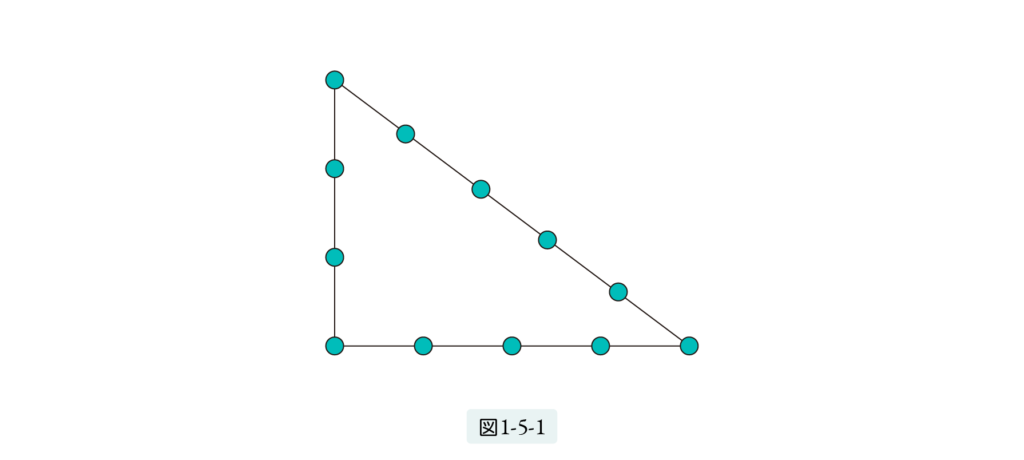

As mentioned earlier, after the Nile’s seasonal flooding, surveyors known as “rope stretchers” played a vital role in redefining farmland.

To divide land efficiently, they needed a way to form right angles.

They would take a single rope, divide it into lengths of 3, 4, and 5 units, and mark each segment.

By forming a triangle using the rope and pulling it taut at the marked points, they could easily create a right-angled triangle.

(See Figure 1.5.1.)

It is said that these rope stretchers used this method to construct right angles.

However, some history of mathematics books assert, “This is just a popular myth,” or even claim “There are no historical records of such a practice.”

These conclusions seem overstated, especially when we consider that many historical records remain undiscovered or unread.

This skepticism likely stems from the assumption that “the ancient Egyptians couldn’t have known the Pythagorean Theorem.”

Yet the fact that a 3-4-5 triangle forms a right angle was known even to Japanese carpenters in the Edo period, and it also appears in ancient Chinese mathematical texts.

Understanding this principle doesn’t require knowledge of the Pythagorean Theorem.

Anyone can draw a rectangle 3 units tall and 4 units wide, measure the diagonal, and see that it forms a triangle with side lengths of 3, 4, and 5.

Once people realize that the 3-4-5 triangle forms a right angle, it becomes a simple and convenient tool, naturally spreading in use.

Therefore, to prove that the Egyptians knew about the 3-4-5 triangle, it is enough to show a single example where it appears.

Such an example, in fact, can be found in one of the papyrus problems discussed in a later chapter of this series.

Early Modern Europe and Shifting Historical Perspectives

In Chapter 1, we explored the background of the “Mystery of the Pyramid,” focusing primarily on its legends and traditions.

Some readers may have come away with a sense of disappointment, thinking:

“So the mystery of the pyramid is just a modern fantasy, born from manipulating numbers and based on mere coincidences?”

However, there is still a greater secret hidden within the pyramid—one that will be revealed in Chapter 5.

That said, the nature of this secret is not necessarily fantastical; in fact, it may be entirely reasonable and grounded.

The reason this truth has remained hidden for so long is likely because we have not truly understood Egyptian civilization.

As Europe entered the early modern era, its scientific and technological advancements rapidly accelerated, and its superiority over Asia became evident to many.

This shift led to a dramatic decline in Europe’s view of the Orient.

With the rise of scientific rationalism, astrology, alchemy, numerology, and other ancient practices were dismissed as superstitious nonsense.

Traditional myths and legends were also cast aside as irrelevant.

Yet, this scientific turn also went too far in some respects.

One such example is Social Darwinism, which promoted the idea that white Europeans stood at the pinnacle of evolution.

According to this theory, Black people were the earliest to diverge and thus seen as the most “primitive.”

Mongoloids, it was claimed, were isolated in the cold regions of Siberia and adapted by developing shorter limbs, flatter noses, and less body hair—not as progress, but as a form of degeneration.

Of course, such claims have no scientific basis, and today, very few people endorse these views.

Still, they reflect the prejudices of the time.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, as European powers expanded into Asia, their true motivation was economic colonization.

However, they justified their actions with the rhetoric of “civilizing the uncivilized.”

In Japan, this idea was not only imposed—it was also actively embraced.

During the Meiji era, Japanese people viewed their own country as backward, and accepted Western civilization wholesale as the model of progress.

This cultural shift was even celebrated under the name “Bunmei Kaika” (civilization and enlightenment).

Nearly all academic disciplines—from mathematics and natural sciences to philosophy, literature, and the arts—came to be built upon European models.

And perhaps it was precisely because of this mindset that Japan was able to modernize so rapidly.

History itself—what we now call “world history”—originally centered on European history.

The term “ancient times” usually referred to Greece and Rome, while other civilizations were treated as supplementary.

However, this Eurocentric view is now being increasingly re-examined.

Take the term Hellenism, which frequently appears throughout this series.

It was coined by 19th-century historian Johann Gustav Droysen, and many scholars have pointed out that it reflects a one-sided European perspective.

Even in the history of mathematics, the Hellenistic and Roman periods were long treated as mere addenda to Greek mathematics.

Yet it is worth noting that the most forceful critiques of this Eurocentrism have come from scholars within Europe and America themselves.